Walk into the Substance Abuse Prevention and Education office in Strom Thurmond Fitness Center and you might find Brock Parrott behind the reception desk.

A 28-year-old social work student, Parrott is in his first year at USC working toward a master’s degree. The reasons behind his employment at SAPE run the gamut, but Parrott’s role in the battle against high-risk drinking among USC students is often forgotten, taking a backseat to the numbers.

The numbers behind USC’s disorderly days and party nights come together down the hall from Parrott’s desk, where SAPE director Aimee Hourigan keeps tabs on the high-risk drinking behaviors of the student body. Binge drinking, blacking out and effects on academic performance are a main focus.

But the trend that caught Hourigan’s eye last month is the sharp increase in the number of USC students landing in hospital beds with alcohol-related illnesses.

According to Hourigan, the number of medical transports for alcohol overconsumption made during the fall 2016 semester was 88 percent higher than in the fall 2015 semester. Worse, she said, the increase during the months of August and September could have been as high as 200 percent. And Hourigan is at a loss to declare why.

“There’s lots of people trying to figure out what’s the cause of that, and I don’t have an answer,” Hourigan said.

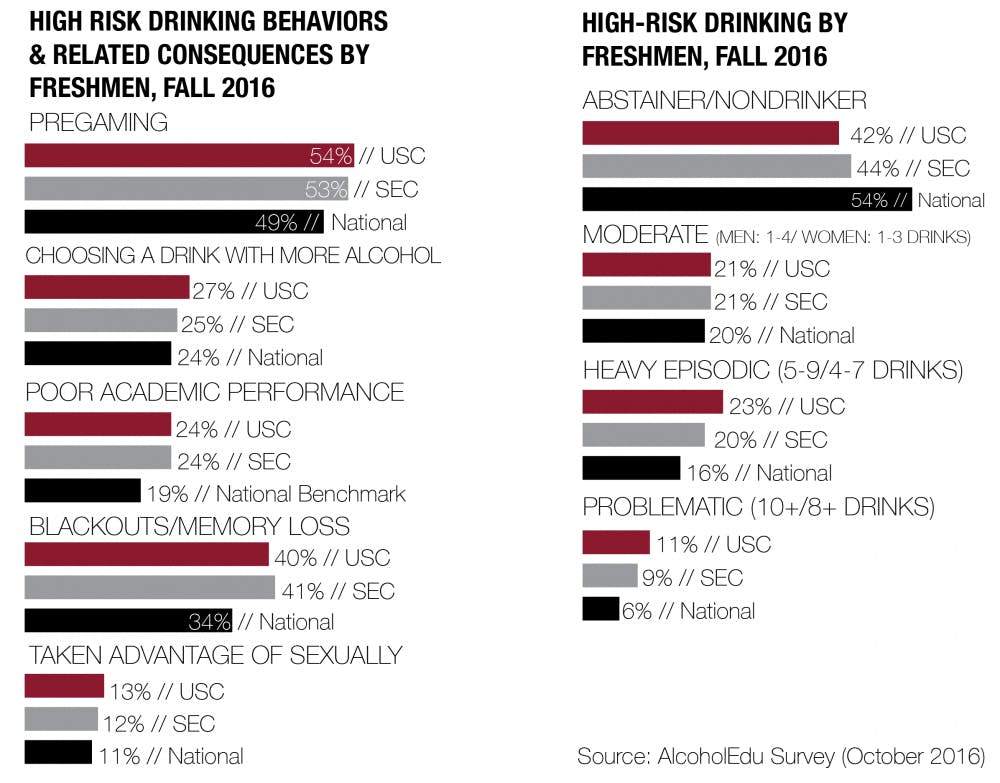

The increase in transports is but one of the troubling trends SAPE has uncovered. According to the AlcoholEdu survey administered to USC first-year students in October, 60 percent of the class of 2020 took part in binge drinking — defined as five or more drinks in a span of two hours — at least once during their first two months. Twenty-two percent had done so three or more times in the preceding two weeks, outpacing the average for Southeastern Conference schools and schools nationwide.

“Our freshmen, those who drink in a high-risk way, drink in a more high-risk way than other SEC freshmen,” Hourigan said. “But how our freshmen this year are different from last year, we’re not entirely sure."

Beyond how they drink, the survey showed Hourigan what happens when members of the class of 2020 drink. Twenty-four percent of first-year students said their alcohol intake had impacted their abilities in the classroom. A further 40 percent experienced blacking out — just below the average for SEC schools — and 13 percent reported being taken advantage of sexually while intoxicated.

However, Hourigan has found that high-risk drinking habits tend to decline with age. Seniors drink more days each week than freshman, she said, but first-year students consume more drinks on each occasion.

Via email correspondence, USC public relations director Jeff Stensland did not reference Hourigan’s figure of 88 percent but said 187 students received treatment for alcohol-related illnesses at local hospitals from August to the end of January, 77 more than that timeframe in 2015-16. He was also quick to note that the number of over-intoxicated students transported to hospitals between the months of November and January declined slightly in 2016-17.

“While the number of students transported represents a very small percentage of our overall student body of more than 32,000, we are very concerned about the underlying problem of overconsumption of alcohol and are taking important steps to address it,” Stensland said.

Regarding the increase in transports, Stensland blamed the practices of bars in Five Points as a main factor, saying the bars shy away from “responsible promotion, sales and service practices” and all but ignore underage drinking laws.

Stensland’s theory is certainly a plausible one. According to October’s AlcoholEdu survey, 37 percent of USC first-years do most of their drinking in bars and nightclubs — nearly twice the SEC mark and more than triple the national average. With the entertainment districts of Five Points and the Vista each walking distance from campus, students don’t have to venture far to find a party.

“There will be fair but clear consequences when poor judgment by individuals or organizations leads to abusive, dangerous or illegal behaviors,” Stensland said of campus alcohol abuse. “When social activities move from fun to dangerous, when they become the backdrop that leads to the abuse of women and when our Columbia friends feel uncomfortable being our neighbors, it’s time for all of us to stand up and say stop.”

But outside of the offices, there is another side to SAPE’s mission. Stories of addiction are often stories of the human condition, of weakness, of redemption. Statistics can only reach the beholder to a point.

To accommodate this, there is Brock Parrott, the young receptionist at SAPE’s main office. From his desk overlooking the indoor pool at Strom, Parrott answers the phone and keeps tabs on appointments. Each day at the desk serves as a reminder of whom he used to be.

A recovering addict, Parrott spent his middle school and high school days drinking heavily, even referring to the period of his life between the ages of 18 and 25 as a blur of drug and alcohol consumption. And when difficulties arose, Parrott’s parents were quick to intervene. This lack of consequences paired with a "pompous prick" attitude meant that Parrott "was coming off the rails pretty fast without even knowing it,” he said.

After departing Midlands Technical College, Parrott’s substance abuse only worsened. He was arrested for driving under the influence in August 2012, and again five months later. Each citation made little difference.

By the spring and summer of 2013, Parrott was a full-on addict and living alone in Irmo selling drugs to get by. He was 30 pounds underweight, living off of freezer-burnt food and finding suicide more alluring by the day. Most mornings, he purchased a Coca-Cola to prime himself for hard liquor, returned home and drank until passing out. He would often repeat the ritual the following day. And the day after, and after that, for nearly a month.

“It came to a point, where it was like ‘There’s two roads,’” Parrott said. “Either I’m going to kill myself, I’m going to die of alcohol poisoning, or I’m going to go do something crazy to get money and wind up in jail.”

Parrott finally agreed to attend a rehabilitation center in Florida. Now back in school and with opioid addiction ravaging American cities, rural and metropolitan, he sees an opportunity to put his experiences with substance abuse to good use. Parrott is projected to receive his master’s degree in the spring of 2019, and he hopes to open a private practice as a substance abuse counselor.

In the work he currently does with Gamecock Recovery, SAPE’s new peer education group, Parrott believes he can divert USC students from the fateful path he took as an undergraduate.

“I am a firm believer that if I had never drank alcohol, or if by some reason something in my body didn’t make me drink alcoholically, I never would have turned to the drugs,” Parrott said.