This is a companion article to "Drug decriminalization would save time, money, human misery" by Linden Atelsek, which ran alongside it in the Oct. 23, 2017 issue of The Daily Gamecock.

Drug addiction has been recognized by public health professionals, for years, to be more of a disease than some sort of abject moral failing. This distinction is important. Every year in the U.S., we send drug users to prison in appalling numbers under the guise of some twisted moral righteousness that places abstract moral positions over the very real needs of those suffering from crippling addiction. We neglect and punish users because we believe that they deserve what they have brought on themselves, despite clear evidence that addiction is often not a choice but a rewiring of the brain.

This state of affairs is untenable. Nearly 64,000 people died last year due to overdoses, and that number is set to rise, yet again, this year. We have to stop pretending that the criminal justice system and our politicians can simply prosecute drug addiction away — there is no evidence to suggest this is even possible. Instead, we should turn to those who know better and a tactic that works: public health and decriminalization.

Public health has always taken a backseat to the criminal justice system and politicians in dealing with the problem of drugs and addiction. Instead of seeking real solutions to problems, district attorneys, and other elected officials, have sought to combat drug addiction via prosecution and imprisonment. At a surface level, it makes sense. Criminalize an action and people will be deterred. Instead, what has happened is massive incarceration with little to show for it. Drug use is still on the rise and deaths are still climbing. Clearly, this path is an exercise in futility. Decriminalization, on the other hand, offers a way out.

Drug decriminalization is the concept of removing criminal penalties from drug use, particularly that by addicts. This wouldn’t, for example, hamstring prosecutors or police from pursuing drug traffickers or dealers; rather, it would turn the attention from the user to the supplier. The supplier would still go to prison, the user would be directed towards public health. In this way, public health would be able to help users break the cycle of use and abuse.

This isn’t some nebulous, untested concept; several countries have taken this path already and the results are impressive. Portugal, for example, achieved decriminalization in 2001 in an attempt to turn towards a more public health oriented response to drug use. As a result, Portugal now has lower imprisonment rates for drug use, better health outcomes for addicts and, most important in the context of the U.S., extraordinarily low rates of “drug-induced deaths.” Much like in our own country, Portugal had massive rates of drug use, particularly opioids, back in 1990s. Drug deaths were high, users were locked up, and treatment was hard to come by. Decriminalization changed Portugal for the better, putting users in the hands of public health professionals and treatment programs instead of behind bars. Users no longer face the agonizing choice of risking imprisonment by seeking help or just continuing on with their addiction.

This isn’t some one country phenomena either. The Czech Republic took a similar approach, with similar results. Drug-induced mortality is low and users have far better health outcomes than in much of the European Union. Clearly, this policy has promise.

To really understand the importance of decriminalization as a drug policy, comparisons need to be drawn to similar countries in the European Union, particularly those with strict drug laws. A cursory look over imprisonment rates, health outcomes and deaths in some of the strictest countries in the European Union makes it clear that decriminalization is an effective strategy. The United Kingdom, Norway and Ireland all crack down on drugs far harder than Portugal and the Czech Republic, yet drug use is still common, health outcomes for users are far worse and death rates are much higher.

When looking over country level data, it is curious that in both countries with decriminalization and those without, drug use is still high. A government study from the United Kingdom noted this well, stating that there was a “lack of any clear correlation between the ‘toughness’ of an approach and levels of drug use.” This finding is important, as it points to crux of the argument for decriminalization — drug use will happen regardless of the penalties, all we can do is save and improve the lives of those who use them. Locking up drug users will not stop them from using drugs and only places a burden on society.

In the U.S., this approach could prove particularly effective. Use rates are either climbing or stable and drug induced mortality is nearing 200 per 100,000 people. These numbers are appalling, especially when you take into account our heavy-handed drug policy. While decriminalization will not impact use, that shouldn’t deter us. There are other programs we can implement to deal with that. It will, however, have an effect on the growing number of dead. Users in the U.S., much like in Portugal, will no longer have to fear arrest or imprisonment for seeking out help and services providing help to users will have a much easier time providing resources.

This is in contrast to our current approach of locking up users. Even moving past the arguments that drug users are immoral and should be locked away, some believe that this course of action actually helps users. After all, they can’t use drugs in prison and their fear of further punishment will put them back on the right track, right?

The truth is, even our prisons aren’t safe from the drug trade. When prisons aren’t neglecting habitual users going through withdrawal, they often fail to offer proper services to help users kick their habit. Even worse, large numbers of prisoners have access to drugs and die from them. The most cruel irony of all though is that, after prison, former inmates are far more likely to relapse even if they do get the help they need. Truly, our approach is failing at even its most basic levels.

This is why a push towards decriminalization is so important in the U.S.; if our current approach is failing, why do we continue the madness? Users are suffering at all levels due to callous policies and laws that neglect the very real impact of public health could have. This is America’s crisis of conscience.

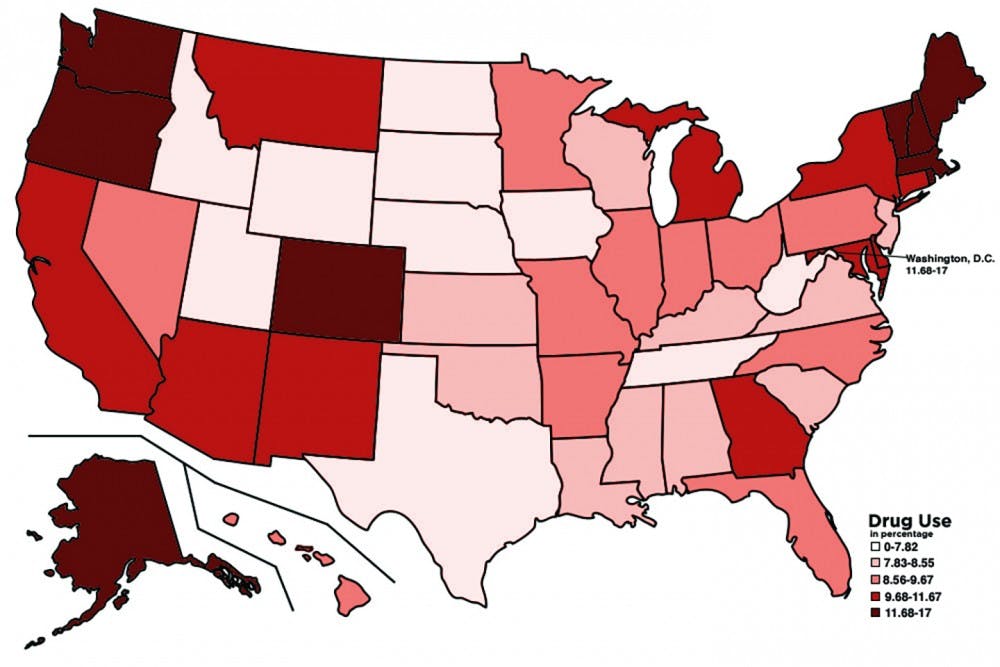

This graph that originally ran alongside this article was incorrect. It has been replaced with the correct graph. The Daily Gamecock regrets our error.