The Internet is uniquely adept at contributing to the death of the people who use it. I am not talking about the health problems that come from sitting in one place too long, nor am I using “death” as some kind of metaphor for screen addiction.

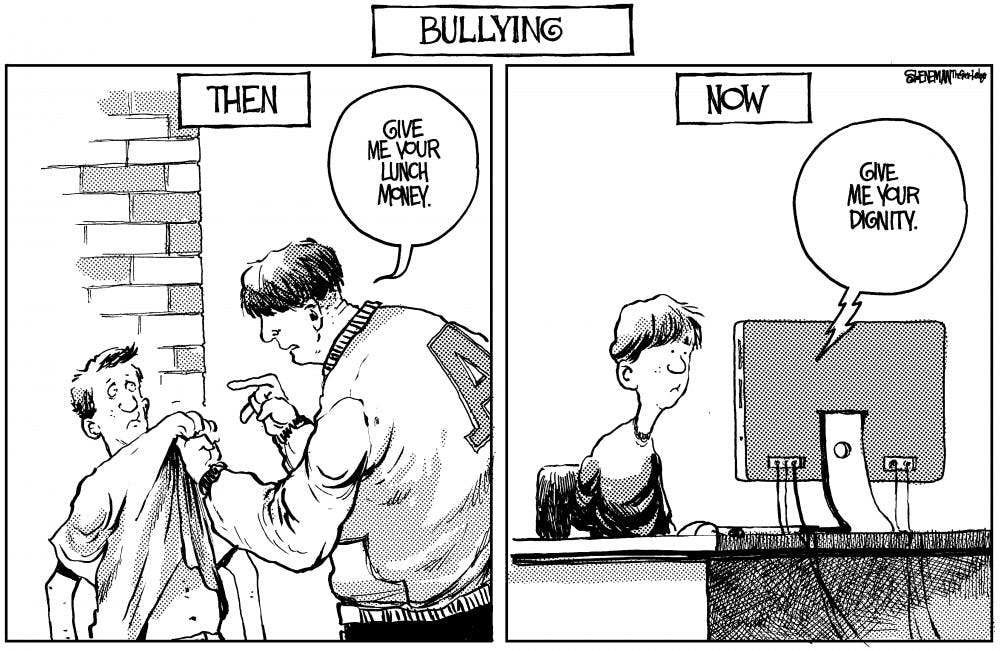

I’m talking about “cyberbullying,” the popular and rather child-like term for the process of contributing to someone’s suicide through a computer.

I myself prefer a older and more powerful word: shame.

Take the case of Ariel Ronis, an Israeli civil servant. In late May, he was accused of racism in the workplace in a Facebook post that was quickly shared thousands of times. He shot himself soon afterwards, denying the events in his suicide letter.

Please note this small excerpt: “Not two days later the post had over 6,000 shares, each of them a sharpened arrow in my flesh. Me? A racist?”

He felt that each person that spread the post was directly responsible for his suicide. I find this hard to accept fully. Only the person who chooses death is ultimately responsible for that outcome.

But the power of something like this to spread certainly played a factor in his death — no one who shared that post is without responsibility. Whether their intention was to change society by using Ronis as an example, to modify Ronis’ behavior, or simply to share support for the victim — this death was the end result.

To them, he was a caricature. An example. A symbol of racism. They saw good and they saw evil. The idea that another human being was on the firing line was not even considered. Neither was that perhaps — perhaps — he could be spoken to like an adult. I feel that a conversation about institutional and unconscious racism might have made him more sympathetic to the narrative of the victim.

In any case, whether Ronis was or was not a racist seems somehow beside the point. The relevant question seems to be this: what actions, if any, warrant shaming?

Arthur Chu, in a column in Salon, said that shaming opponents of gay marriage played a significant role in bringing about a change in public opinion and that the ends justified the means.

This is an interesting idea, and leads to a larger question: in what manner should we change those whose opinions we find abhorrent?

There are plenty of these opinions circulating on the Internet. Wouldn’t an effective way to modify behavior be to retweet it, so that all of the people who agree with you can have their turn to be disgusted? (And doesn’t it feel so very good to be disgusted?)

Whether or not shame is effective does not concern me. Shame is not argument. It is manipulation. Shame does not change a mind; it bends it unwillingly under the force of the multitude.

Where argument and adult discussion can lead to change, shame pushes those beliefs deeper into their psyche, fostering resentment and hatred.

In the same way that fat-shaming does not lead the shamed to engage in healthier behavior, it seems likely that shaming racists doesn’t make them any less likely to give up their beliefs.

My reply to Chu would be this: public support for gay marriage did not jump 33 percentage points in less than two decades because Christians were afraid of being called homophobic.

It changed because Americans came to terms with a simple truth: Love works in more ways than one, and deserves equal respect.

But, for the sake of argument, let’s say that shaming does work. If the only course of action we took was to shame the people we disagree with, any victory we achieve will be temporary. The effectiveness of shaming is only as powerful as the group that constantly reinforces that shame.

A hypothetical: If the majority — say 70 percent — of the U.S. populace were members of PETA, everyone but the most die-hard carnivores would be too ashamed to enter a burger place. Whole new underground beef delivery systems would have to be developed for that 30 percent. Packaging and shipping industries would need to arise to send pork chops discreetly, in unmarked boxes, in the same way that sex toys currently circulate through society.

Were PETA to lose popularity, however, the stigma of eating meat would disappear and burgers would be as popular as ever. The change, while arguably good, could not last because it relied on the power of the majority to shame its opponents. And, in democratic societies, people can change their minds very quickly.

As the gay marriage debate has conclusively shown, people are open to accepting new ideas if their truth is obvious. The American people, somehow, were convinced to come to its senses. That’s why gay marriage is here to stay.

Argument is the method that we can use to make those truths more clear. And truth, unlike shame, does not rely on who has the most voices.