To teach or not to teach Shakespeare? That is the question.

Shakespeare should be taught in schools.

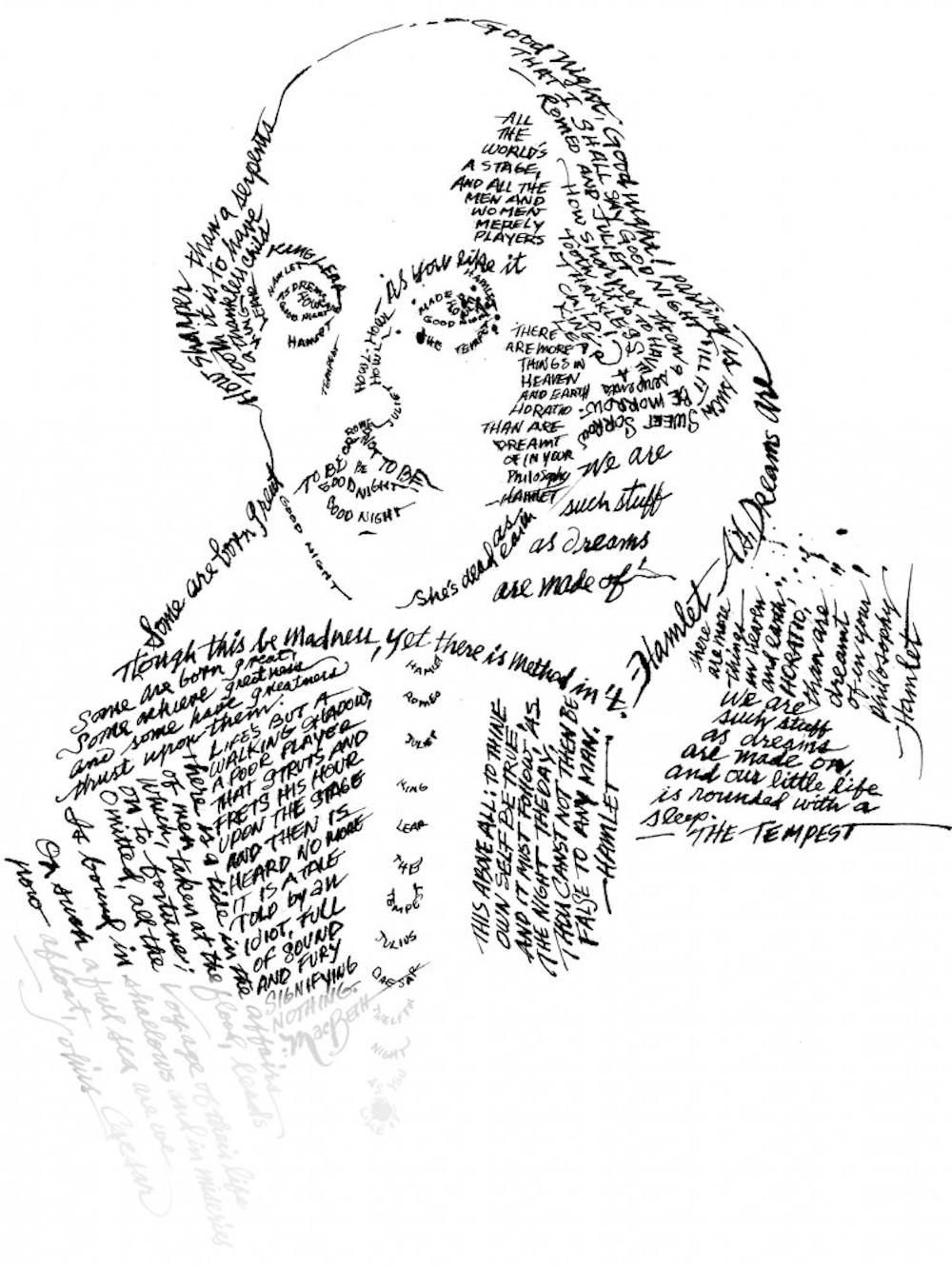

You may have seen in the news recently the discovery of another First Folio, a first edition volume of William Shakespeare’s plays, or perhaps heard that this April marks the 400th anniversary of his death. Practically everyone reading this sentence has been exposed to the work of the great English playwright William Shakespeare. You probably read one or more of his plays during a high school English class and, if you were anything like me, wouldn’t have minded never picking his work up again. If most of us didn’t like Shakespeare, why should we make the next generation of high schoolers endure a regimen of works that seem to be made up of confusing language, ridiculous characters and either a nonstop barrage of bawdy jokes or oppressive doom and gloom?

Let me begin by noting that the reading of books in general has decreased in the face of increasing technological absorption. When I ask my friends what books they have been reading lately, the answer is generally, “I don’t have time to read.” This is probably true for the given college student if they make no changes in their other sources of recreation. Studies show that female college students are spending an average of 10 hours a day and male college students an average of eight hours a day on their phones. It is undeniable that scrolling through status updates is easier than engaging with great literature. Reading humanity’s classic works takes dedication and a willingness to stick with something unenjoyable until we learn to enjoy it. If we follow the path of least resistance we will end up on our phones most of the time, joining the 54 percent of Americans who, according to 2014 polls, read five or less books a year.

The phenomenon of constant social media use creates the effect of an echo chamber, where our own world views, ideas, hopes and struggles are endlessly cycled back to us. We exacerbate the effect by selectively "friending" or "following" those who are ideologically similar to us, ensuring that we never hear anything really challenging or conflicting. This is the danger we face in abandoning classic works like Shakespeare’s.

If we restrict our consumption to the media being produced by those of our own generation, we lose any opportunity to consult the wisdom of past ages. If we do not return again and again to the classics, we will soon forget that there is any other way to approach a matter than that dictated by current public opinion. The true value of the classics lies in this reminder that we are not the first to discover life under the sun or contemplate its mysteries. They deconstruct our misguided belief that we are the most enlightened and advanced generation ever to exist.

Popular interest in the great literature that has defined our civilization seems to be diminishing in this technologically preoccupied age. But if we stop teaching Shakespeare to the generations that follow us, we will be sawing away the cultural branch we stand on. We will be cutting ourselves off from the insight of past generations and refusing to acknowledge the cultural and artistic foundation upon which much of our literature and worldview has been built.

Shakespeare should not be taught in schools.

Most people here probably didn’t get to college without having to read at least one of Shakespeare’s plays.

But why are we so hell-bent on teaching the Bard?

Some say there’s inherent value in teaching classics. Others will point out that Shakespeare has been commended for his command of language generally. And, of course, he’s been an enormous influence on the progression of literature.

It’s hard to argue that Shakespeare wasn’t a master of the English language. Although I’ve never really liked his plays, they contain some of my favorite quotes. But it’s also hard to argue that he’s the only author who can be studied to learn nuanced word choice. In fact, with many students confused by what his words mean, some of the punch is taken out of them because of the effort it takes to understand them.

Of course, there’s no reason that, for college students in English or literature majors, the difficulty of Shakespeare’s language shouldn’t be a minor obstacle on the way to grasping a vital part of literary history. But for students in high school, who are in English class primarily to learn foundational reading comprehension and critical thinking skills, struggling through vital parts of literary history is perhaps less important than learning basic literary analysis in a setting where they actually stand to fully comprehend it.

It’s like a joke — once you have to explain it, it’s not funny. It’s hard to focus on Shakespeare’s skill at punning when your teacher or No Fear Shakespeare needs to explain what “maidenhead” used to mean.

There’s no reason Shakespeare ought to be special in our education. On a list of 100 classics, which clearly doesn’t include everything in the Western literary canon, there are quite a few I don’t remember my high school teachers ever mentioning. Yet, in school, I had to read not one, but eight of Shakespeare’s plays. An overflow of good converts to bad.

Why the undue emphasis on Shakespeare? If it were just a classical education we were after, why did my classes never touch Marlowe or Hugo? I don’t recall another author that I had to read more than one book from in high school, but I was taught Shakespeare more than once a year on average.

It's arguable that learning the classics better prepares you for the books that come after and reference them, but on the other hand, when was the last time you saw a Shakespeare reference that required knowledge of the plays that was more than superficial? No one ever references the Porter, obviously drunk — usually the most you have to know to understand allusions to Shakespeare is that Romeo and Juliet were star-crossed lovers and everyone dies in Macbeth. And, for the most part, these are things that you know without reading the plays.

We’re so focused on the classics — on Shakespeare and Homer and Chaucer — that we don’t bother teaching students anything new. The most recently published book I read in high school English was 55 years old. So, it’s not so much that I have an objection to teaching the classics as I have an objection to only teaching the classics.

There are newer "classics" that never make it to the desks of high schoolers, and by refusing to teach them, we’re devaluing the more recent evolution of literature. Until high schoolers start seeing Neil Gaiman and Donna Tartt in class, I’m not sure we need to see the Bard there, either.