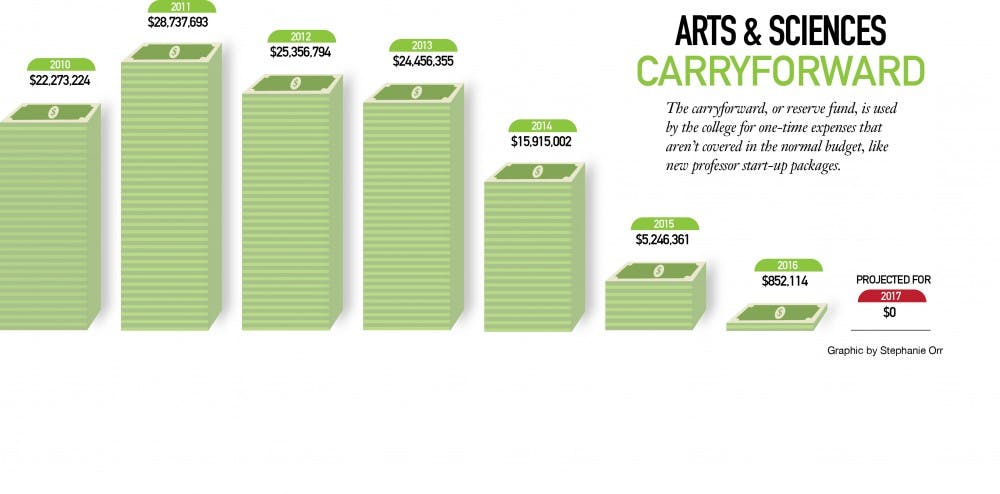

College of Arts and Sciences Dean Lacy Ford was brought in this July with the largest college in the university facing an unfamiliar challenge: a complete lack of carryforward funds projected into the next fiscal year.

As recently as 2011, the college had $28.7 million in the carryforward fund. “When I came in … that money had been spent," Ford said.

The college had routinely been operating with a spending deficit and pulling from the fund to cover the shortfall. Now, Ford has to balance the budget by whatever means necessary, and he's being told to do it without help financial assistance from the university.

The effects could go far beyond the carryforward fund to affect students and faculty.

In an email sent to faculty earlier this semester, Ford said there was no money for facilities, no money for new faculty startup packages and "insufficient funds to meet all of the College’s existing commitments.”

The most common question that people seem to be asking is, “How did this happen?”

Professors and department chairs alike weren’t even aware that anything was wrong until a meeting with Ford and the chairs in late summer. But the reasons for the dwindling funds began years ago.

“We’re in a real interesting budget time. If we go back 10 years, the state provided 20 percent of our budget, which is significant,” said Augie Grant, chair of the faculty senate. “During the Great Recession, they cut more than half of their funding.”

This year, state funding accounts for 10.5 percent of the university budget. At the same time, the university budget has mushroomed 50 percent in the past seven years.

The previous arts and sciences dean, Mary Anne Fitzpatrick, recruited 300 tenure-track faculty and was instrumental in the establishment of many new institutes and programs during her 10 years at the helm. She was recently named interim chancellor at USC Upstate.

“So that money (the carryforward funds) had been spent down in a fairly rapid pace because the university was in a period of doing a large volume of hiring from 2011 through 2015/16,” Ford said.

The university says that the spending was done intentionally and strategically. However, two professors, who both wished to remain anonymous because they were afraid of repercussions, expressed concerns with what they perceived as reckless spending.

“Dean Fitzpatrick just made vast over-commitals and then took off,” a professor of mathematics said. “Meanwhile, she ran the College of Arts and Sciences into the ground, and deep underground.”

A English professor said, “I think it’s fair to say that reactions to this news in our Department meeting ranged from stunned silence to angry outburst.”

The implications are severe for the university’s ability to hire new faculty, at least during this fiscal year. While there isn’t a complete moratorium on hiring, the lack of funding for startup packages that are always provided to new faculty greatly restricts the ability to attract new faculty. These startup packages can range roughly from $25,000 for a historian to $500,000 for a chemist, according to Ford. He hopes to be able to resume normal hiring as soon as possible.

One of the other actions was a blanket 10 percent operating cost cut across all 19 departments.

“In my experience, most organizations can stand a one-time 10 percent budget cut,” Grant said.

Operating costs are only about 10 percent of each department’s budget and cover things like faculty travel, graders and printers.

“To be honest, some of the impacts are potentially positive in the sense that it’s forcing people to economize in ways that they probably should have been already,” philosophy chair Michael Dickson said.

Dickson is strongly encouraging his faculty to become paperless, a move that he already wanted to make but is now necessary because of the operating cost cut.

The math professor voiced strong concerns about the potential loss of graders. He said that the result would be fewer assignments and less feedback for students.

“That, actually, I have a very serious problem with,” the professor said. If implemented, “it’s going to have a huge impact on the education experience people have going through the math … sequence.”

Ford has also focused on the consolidation of funds to be under the college rather than the departments themselves.

Previously, temporary faculty were paid for by their respective departments. Now, Ford said, the college will be running the hiring of temporary faculty. He is predicting up to half a million in savings from this action due to potential increased efficiency.

Another change is in the tuition reimbursements given to departments for graduate students, who don't pay for classes. The college had been providing reimbursements, known as abatements, equivalent to 18 credit hours per graduate student. Now, the departments will only receive abatements equal to 15 credit hours. Ford said that the average graduate student at USC takes 14.7 credits and that this measure shouldn’t affect many of the 1,217 graduate students in the college of arts and sciences.

According to Ford, the departments were keeping additional funds left over from the abatement money, partially to help pay for the temporary faculty that will now be paid for through the college.

However, for many departments, the biggest will come from a different consolidatory reform: moving revenue from Honors College classes from the departments to the college. Ford said that Honors College Dean Steve Lynn approached him and asked for “centralized incentives for offering Honors College courses.”

The Honors College previously dealt with each department individually to arrange honors classes. Under the new system, centralized incentives provided to the College of Arts and Sciences are then divided equally into money to be saved and money to be dispersed to the departments. The College of Arts and Sciences has been saving half of the money provided from the Honors College, according to Ford.

While departments will likely have the opportunity to receive up to half of this funding back, the short-term effect is a significant loss.

And for some departments, that money was much more than 10 percent of operating costs. According to the associate professor, the Honors College money accounted for more than half of the mathematics operating costs.

Professors and departments that had saved up funds and been fiscally responsible, whether in personal professional development funds or the departmental carryover, have essentially been told that money is no longer available.

“To be honest though, because of what happened this year, our department — and I suspect the same is true of others, but I can’t speak for them — is gonna be less inclined to save money, because now we know if we save money in one year, we might be told, ‘Sorry, you don’t get that,’ in the next year, which is what happened this time around,” Dickson said.

Dickson had saved "tens of thousands of dollars" last year in order to fund a biannual philosophy conference that will no longer be held. Other departments are also still waiting to hear if they will be able to hold planned events.

Many of the changes implemented by Ford will be up for debate over the next few weeks as he goes around to each department individually.

“We see the university making huge investments in things like the Student Success Center, the University Advising Center (UAC), the new health center — these are things we know we have to have to be a 21st-century university. None of that puts professors in the classroom. That’s a realistic thing,” Grant said. “The bottom line is the university has to choose where to spend its money.”

And the university has chosen to have Ford see what he can do for the College of Arts and Sciences without external financial support from the university.

"People who run the university who make the decisions about how to allocate funds need to decide if they want to run an educational and scholarly institution or a business," the mathematics professor said. "And if it’s a business, then maybe we should just cut all the unprofitable departments.”

While obviously no one can predict exactly how the changes will play out, every single person spoken to emphasized how the mission is and always has been the students. Both administrators and faculty were focused on making sure none of the changes impact students — even if there are disagreements over the process. Ford is confident the changes will be beneficial for the university in the long run.

"I hope [next year] we’ll be talking about the books that our faculty has published and the big grants they have gotten,” Ford said. “And I hope they’ll be saying we’re financially well-managed and that if we have a problem, we’re addressing it.”

Features editor Emily Barber contributed to this report.