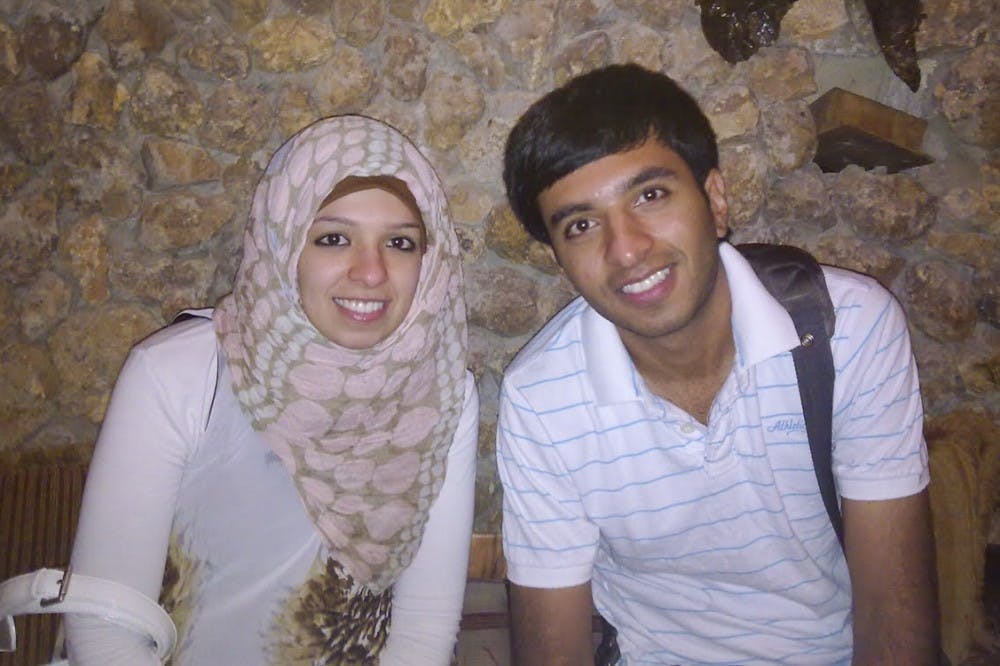

The last time Zaid Alibadi saw his sister was three years ago. He was working for the U.S. embassy in Baghdad, and he had started receiving death threats for associating with Americans. When it got dangerous, he knew it was time to leave. He got a student visa and is now earning his doctorate in computer engineering from USC. But the threats were against his family as well. His brother and mother were able to come to the U.S. this summer as refugees, but his sister, Shahad, is still waiting in Iraq.

“I am feeling like this is my fault because I made all my family change their life,” Alibadi said.

An estimated 90,000 people are directly impacted by President Donald Trump’s executive order halting travel to the U.S. for citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries. But this estimation includes only people who have already been granted visas. For those still seeking approval, the 90-day ban represents what could be a much longer period of doubt. And the executive order extends the entry ban an extra 30 days for refugees, meaning Shahad will be waiting at least 120 days.

This uncertainty is what worries Alibadi. While he's been in Columbia since December 2013, the process to immigrate as a refugee takes multiple years. His sister, her husband and their young child were hoping to soon be accepted before the travel ban was announced.

“I’m relieved that my mom and my brother are here, but at least at the same time when my mom was there with my sister, she was taking care of her,” Alibadi said. “But now she’s alone.”

Alibadi has a long history with the U.S. government. After working for the U.S. Army in Iraq, Alibadi worked in Baghdad recruiting locals to work for the U.S. Embassy following the troop withdrawal. To work for the embassy, he had to go through extensive security checks, including the investigation of 50 of his closest family members. As a staffing site manager, he left the “green zone” — the safe area of Baghdad — to find candidates who didn’t pose any risk. He interviewed over 1,000 Iraqis, by his estimate. And as he became known as an American associate in the area, he started to receive death threats from Iranian militias. The threats targeted his entire family. They were forced to move several times, and his sister could still be in danger.

Many of his colleagues and friends are still in Iraq, now unable to travel to the U.S. Alibadi said that several reached out to him about the order, including a friend who works for Exxon Mobile and was supposed to be coming to America for training on Feb. 2. Because of the long history of American involvement in Iraq, there are many jobs offered by U.S. companies and government organizations.

“Working with the Americans is one of our dream jobs; you feel that you really make a difference,” he said.

One benefit of working for the U.S. government is the ability to apply for the refugee program. This allowed employees and their families to leave if they were in danger — an option that is now in doubt. Although the Trump White House has requested that the Pentagon compile a list of Iraqis who work with the U.S. armed forces to be considered for exemption from the ban, there is no evidence that the list currently includes family members.

Out of the countries included in the ban, Iraq has the closest ties with the U.S. Alibadi said that "it is a mystery" why Iraq was included in the ban.

“We are fighting this war together,” he said. “But now, a lot of my friends who are talking with [Americans in Iraq] since last weekend are saying, ‘We feel like we are the enemy now.’”

An official recommendation from the Iraqi government to consider an effort suspending all visas for American citizens shows that the anti-American faction has gained traction. In addition to private contractors and businesses, there are over 5,000 American troops deployed in Iraq to assist with the fight against the IS whose position in the region could be jeopardized.

For them, just like Shahad waiting to get to safety and Alibadi waiting to see his family reunited, the situation is uncertain.

“This is not only about me; I’m just one story of tens of thousands,” Alibadi said. “I’m just lucky that I’m here.”