Every year, 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke. That's one every 40 seconds.

People who survive a stroke often have some form of motor impairment, whether that be difficulty organizing their eye movements or their ability to move their limbs or both.

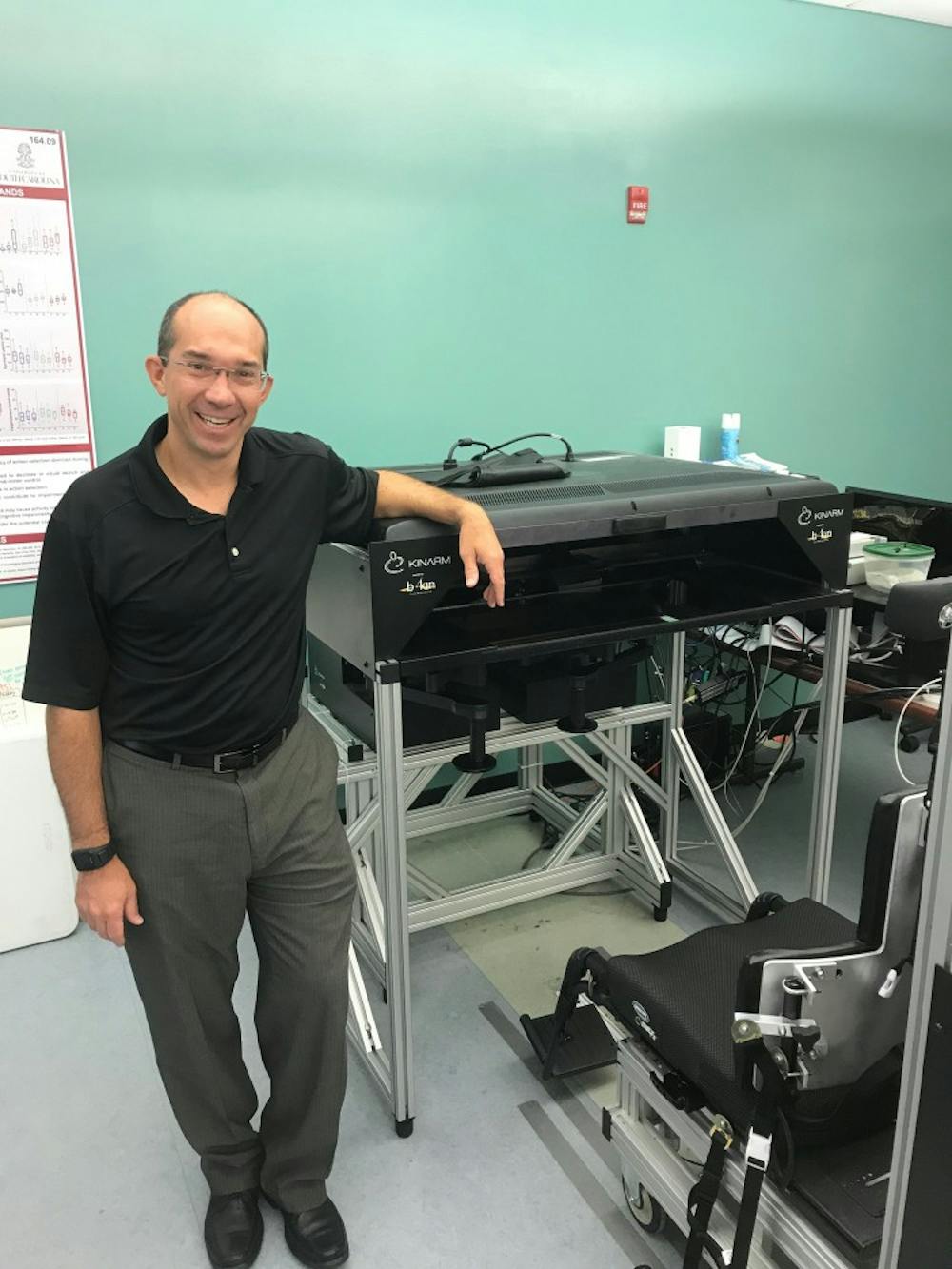

Troy Herter, graduate director and the head of the rehabilitation sciences division at the Arnold School of Public Health, recently received a grant from the American Heart Association to investigate the correlation between post-stroke patterns of motor impairment and self-reported patient disability.

To better understand eye and limb movement in these patients, Herter will be utilizing an upper extremity robotic apparatus. This robot allows patients to be seated in a chair while holding onto robotic handles and brings them into a virtual environment. In this environment, robotic motors can measure where a patient’s hands are in space at every moment in time, how fast they are moving, if they are accelerating and what direction they are moving. Simultaneously, an eye tracking system records where the patient is looking at all times.

Once the patient has entered the virtual environment, Herter will run them through several tasks ranging from mundane activities to complex simulations that require very fast eye and hand movements and quick decisions about when, where and how to move.

“We can take those measures of limb movement or measures of eye movement and correlate those across to difficulties with daily activities and driving and where the legions are in the brain and the differences in connectivity compared to normal within the brain and put together this picture of how does the brain control movement? How does the brain integrate organization of eye movements with limb movements and what does this tell us about rehabilitation?” said Herter.

Herter will also be performing neuroimaging on these patients. This neuroimaging in combination with the robotic data and self-reported disability questionnaires will allow Herter to put together a more holistic picture of the effects of stroke and then this information can be used, in turn, for better rehabilitation of stroke survivors.

“[The brain] is all about networks of interconnected regions that work together as a single connected unit to distribute the processing power across many different areas,” Herter said. “What are largely segregated, certain nodes or certain areas within two different networks, say those involved in eye movements and those involved in limb movements, may actually overlap between the two and become important hubs for integrating the two together to generate the type of behavior and be able to perform the types of tasks that we need to perform.”

Armed with his grant from the American Heart Association, Herter is attempting to better understand this neural connectivity to benefit post-stroke patients with motor impairments. He recommends undergraduate students get involved in research by knocking on doors, talking to professors and finding what truly interests them.