This is a companion article to "Drug decriminalization puts public health ahead of politics" by Dan Nelson, which ran alongside it in the Oct. 23, 2017 issue of The Daily Gamecock.

Contrary to popular belief, the United States does not have the highest incarceration rate in the world. That honor goes to the tiny island nation of Seychelles, which locks up 738 people per 100,000. Comparatively, at number two, we only jail at a rate of 666 people per 100,000.

But before we start patting ourselves on the backs for losing to a country that’s home to a 700-pound tortoise and a jail full of Somali pirates, we should probably look at the rest of the facts. Like the fact that our next closest competitors for the crown by rate are El Salvador, a country known for violent street gangs, and Turkmenistan, an authoritarian state, and our next closest competitors by total number of inmates are Russia and China — two more authoritarian states. Or the fact that we account for more than a fifth of the world’s total prison population.

It wasn’t always this way. Mass incarceration is a fairly new problem. The spike in our prison population has happened in the last forty years, skyrocketing by 500 percent since the early '80s, when Reagan kicked Nixon’s war on drugs into high gear. The steadily tightening strictures of drug laws hurt everyone — the people arrested, overwhelmingly for simple possession, who have their lives disrupted, often harmfully; the people convicted, who can be fined money they don’t have or locked up; their families and communities, who suffer from their loss; and even the justice system itself, which wastes a tremendous amount of time and money (about $571 billion since the '80s) arresting, trying and imprisoning drug offenders.

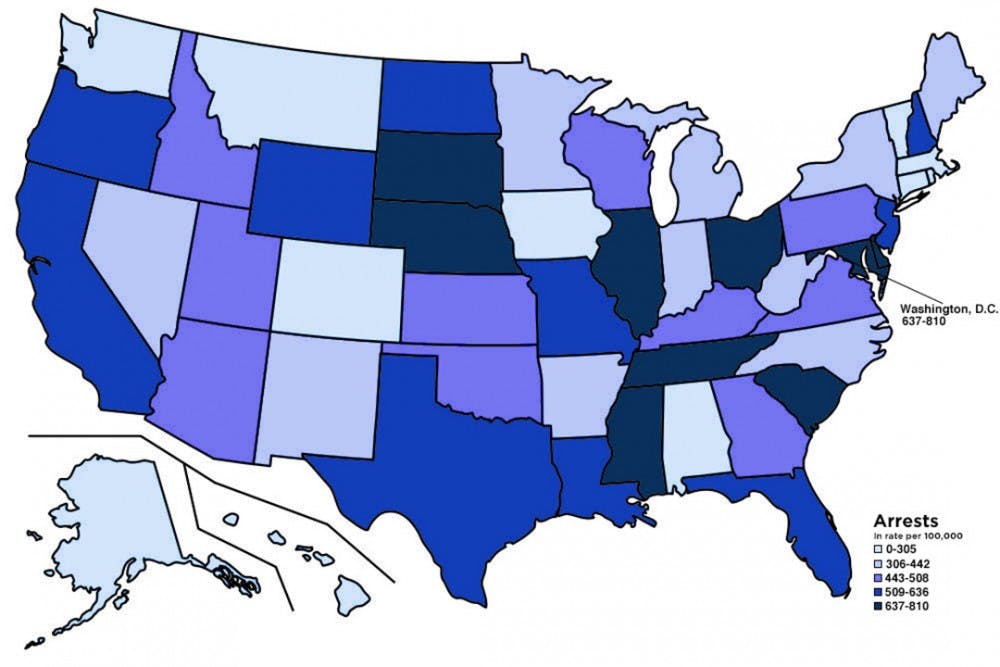

In 2014, more than 1.5 million people were arrested for drug law violations — nearly 84 percent of them for simple possession. At every step of the process, that number puts strain on the justice system. Cops who are picking up people with a syringe full of heroin or a joint in their pocket could undoubtedly be doing something better with their time, like raising our generally low clearance rates. Jails are over capacity. Public defenders, who handle 60 to 90 percent of defendants, are sometimes forced to take on more than twice the recommended number of cases to keep up with the number of people being tried. Our justice system is in crisis, and it’s taking it out on the people it’s meant to serve, both in pain and hassle and in tax dollars. This overload costs us $215 billion a year.

There is a quick and easy way to relieve some of this congestion: decriminalization or even full legalization of controlled substances. Even with simple decriminalization, which leaves trafficking and dealing laws still fully in place, a more than 80 percent reduction in the number of arrests per year would go a long way towards reducing the burden of the war on drugs on the justice system, and in turn reduce the burden of the justice system on the general public.

One of the biggest problems with suggesting something like that is the way we view drug use. Like most other crimes, we see it as a moral failure. Decriminalization is saying that we, as a society, are OK with that. Leaving aside the fact that addiction is an illness, which, morally, we probably should not be punishing, there are a few other things to consider before dismissing the idea on those grounds.

First: Should we be legislating morality at all? The answer is obviously yes when we’re referring to violent crime and property crime — those laws are there to protect other people and their property from you. Depending on your political bent, the answer is also obviously yes when it comes to things like tax law — those laws are there to protect society from you. But drug possession laws are there to protect you from yourself, and it’s questionable whether the government should have the responsibility, or the authority, to do that for you.

Second: The immorality of drug use is largely a modern view, so it’s important to take a critical look at why we’ve grown to believe it. Most of the “big bads” we hear about in the news today — like cocaine, heroin, marijuana and methamphetamines — were once used casually for recreational as well as medical purposes.

I’m not saying we should make a return to the bad old days of opium dens and Sherlock Holmes taking a little cocaine to unwind. It’s clear that 150 years ago, we didn’t know all of the negative effects these drugs could have. But, importantly, we didn’t outlaw them because we suddenly got wise to those effects. We outlawed opium in the late 1800s because the Chinese were doing it. Then we outlawed cocaine because black people were doing it. Then we outlawed pot because Mexicans were doing it. We have routinely criminalized the way non-white people do drugs more often and more harshly than the way we have criminalized the way white people do drugs — never more obviously than in the case of the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine.

And, incredibly, although white and black people use drugs at the same rate, and white people are more likely to sell drugs, black people are still much more likely to be arrested for drug crimes. Part of that is systemic racism that has nothing to do with drug laws, but we shouldn’t take it for granted that drug laws written in the spirit of racism have nothing to do with current racial disparities in enforcement.

Another reason to decriminalize or legalize is that, even if we want to pretend we made the laws to lower crime rates, they probably don’t do that. Americans need look no further back than Prohibition to see a Technicolor illustration of this. While alcohol use did drop after we made it illegal, there was still a significant portion of the country that still wanted to get drunk, and since there were no longer any legal establishments able to satisfy that demand, organized crime rushed in to fill the void. Violent crime rose, prison populations swelled, police and government corruption ran rampant. Likewise, the war on drugs gave birth to drug cartels, which currently control our drug market and have driven violence in Mexico to record-breaking highs.

Decriminalization isn’t a cure-all for the ills of the justice system. But it would save it a lot of time and money and lessen some of the injustices created by our current laws, which have also contributed to cartel violence at home and abroad.

The real question is: Can we get over ourselves long enough to do it?