The political podcast — it’s a format you know well. It most commonly features a business-casual man at a desk in front of a green screen loudly monologuing into a large condenser microphone. Often the monologue will retread ideologically familiar territory like the degradation of traditional family values or the federal government’s perversion of the Constitution. Without even mentioning names, this description has probably brought someone to mind.

The presidential election helped expand the reach and perceived legitimacy of these Internet shows — who can forget President Trump’s shout-out to and press credentialing of Alex Jones and InfoWars? As accusations of “fake news” marred major sources like CNN, the podcast format became a popular alternative. They were an attractive option because they seemed like a hip, rebellious way to overthrow the authority of the mainstream media and its corporate overlords.

However, regardless of whether or not you agree with the views of these online commentators, it’s ignorant to assume that these alternative media outlets are independent of a corporate agenda. In fact, some of these outlets seem to keep a firmer grasp on their commercial interests than do most major news outlets.

Commentators realized a long time ago that the sorts of people who trust alternative sources of news are extremely easy to sell to. The strategy is simple: terrify the listener, convince them that your product will bring them security and emphasize the importance of acting quickly.

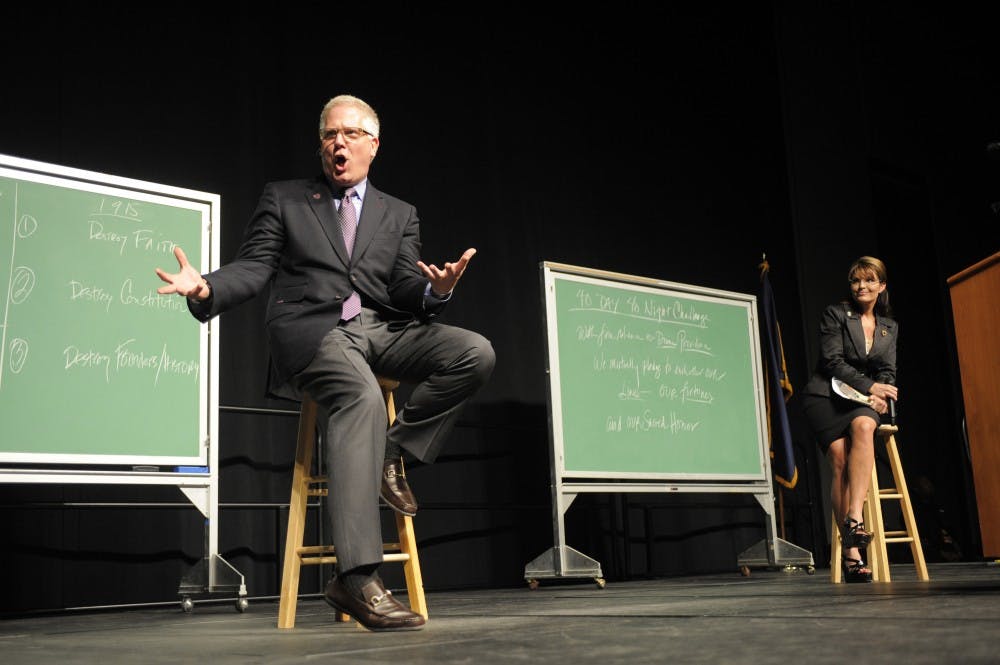

Glenn Beck was a master of this technique in the early days of the Obama administration. He prophesied social and economic turmoil while expressing how crucial it was for his listeners to buy gold coins from his sponsor Goldline before what he implied would be the illegalization of precious metals ownership. It was a successful ruse to be sure, but it wasn’t long until customers noticed the high markup and low resale value of the coins and the scheme prompted a legal investigation. The podcast business model needed a way to detach themselves from large corporate sponsors.

During election years, people wear their ideologies on their sleeves. Political rallying cries like “All Lives Matter” and “Hillary for Prison” grace the front of T-shirts and the bumpers of cars. People have strong opinions and are willing to spend money to make sure other people know. At some point, this must have triggered an epiphany among podcast commentators: why rely heavily on corporate sponsorship when you can be your own brand? Alex Jones’ InfoWars is emblematic of this spreading philosophy.

Like Glenn Beck, Alex Jones is not shy about preaching forthcoming doom and gloom, but unlike Beck, Jones focuses most of his endorsements on in-house products. On the InfoWars webpage, next to the news coverage, there is a store replete with slogan apparel, survival gear and health supplements. With such a direct incentive to market product, it’s easy to become confused as to whether a story is news or just a protracted advertisement — is a piece about juice boxes turning children gay “news” or an effective plug for the InfoWars Super Male Vitality elixir (available now for only $59.95)? I think Jones' reported $10 million earnings offer a pretty resounding answer.

This isn’t an attempt to make a sweeping attack on alternative media or to protect the reputation of mainstream news. My point is that it's important to be suspicious of anyone who points out a problem and has monetary attachment to the solution. Don't be naive and assume that they’re giving you advice out of the goodness of their hearts.

There’s nothing wrong with repping a product; it’s in the best interest of these commentators to do so. It becomes wrong only if you let them convince you that it’s in your best interest too.