Minority groups — particularly African Americans and refugees — are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 through program disruptions, ability to social distance and access to healthcare.

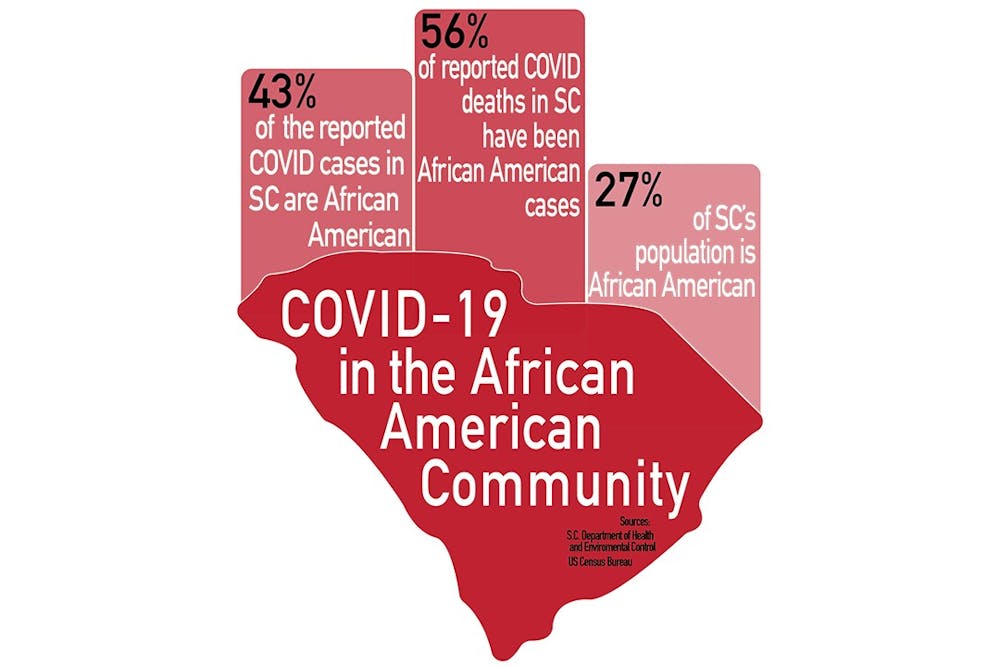

According to the South Carolina DHEC website, of all reported cases of COVID-19 in South Carolina, 43% have been African Americans.

"In South Carolina, as well as the U.S. in general, the minority population are the ones that struggle mostly with poor health outcomes, okay, because there's a lot of health disparities," Edena Guimaraes, a clinical assistant professor in the Arnold School of Public Health, said.

Jason Cummings, an assistant professor of sociology and African American studies at USC, said in an email interview not everyone has the ability to social distance.

“For most Americans and South Carolinians, working from home or social distancing is really a privilege the people have if they have the resources, the job flexibility and live in the right neighborhood to do so. This is not a privilege available to many African Americans or low-income South Carolinians,” Cummings said.

Dr. Rajeev Bais, the director of the Carolina Survivor Clinic, said members of the refugee population are struggling with their financial situation, which makes it hard to access the physical care they need.

“Many of them — not all of them — many of them are struggling because, you know, you come to this country, you don’t know English, you don’t know the customs, you probably don’t have the best education or skill set. You come to the country, and you work hard, but you're put into these manual labor jobs, which are very insecure,” Bais said.

Even with the financial means, it is often hard for minority groups to seek healthcare in rural areas.

“In South Carolina, for example, we’ve seen four rural hospitals close in the last 10 years, and so that makes it a challenge for people to access care, or they might have less access to a hospital,” said Whitney Zahnd, a research assistant professor for the Rural and Minority Health Research Center in the Arnold School of Public Health.

African Americans make up 27.1% of South Carolina’s population, and they account for 56% of the reported COVID-19 deaths in the state, according to DHEC.

“These racial health disparities that we see are not new, nor are they unique to COVID-19,” Cummings said. “African Americans across the country and within our state are more likely to die from a range of health conditions, and many of these excess deaths could be avoided if we focus on addressing some of the underlying social conditions.”

Cummings said some of these underlying social conditions include poverty, health insurance, air and water pollution, health and uneven access to quality education.

The pandemic has also disrupted access to resources. The Carolina Survivor Clinic provides support to refugees by offering tutoring programs, English classes, art classes and a quasi-legal program to help refugees attain citizenship, along with healthcare services. The clinic is still running its healthcare programs, but community programs that many refugees depend on have been suspended because of the coronavirus.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about when we're going to start our programs again,” Bais said.