Renaming buildings on campus or taking down statues shouldn’t be hard, yet here we are.

Before it was taken down on June 24, the statue of John C. Calhoun towered over Charleston at 115 feet. Every time I went downtown, it was uncomfortably hard to miss. It made me uneasy, seeing the monument depict a guy who thought slavery was the coolest thing before sliced bread. Nearby, a street still bears his name.

Now what does it say if I, a white person, find that uncomfortable? Worse, what does it say if, since its erection in 1896, the city of Charleston decided Calhoun was the best person to have the most visible statue of?

Changing the names of buildings and monuments is not erasing history, but rather it is illuminating the parts that have always been there and quieting the parts that we, as a society, have agreed to find repulsive. This state is home to so many people on the right side of history, so one should wonder why we honor slaveholders, segregationists or those who, at the bare minimum, had terrible professional ethics.

Regardless of what some say, naming a building after or having a monument of someone is not simply “remembering history.” It is honoring someone, glorifying both them and their beliefs and actions. That is what naming something after someone or erecting a statue of them means. So why must we remember people who, by all modern accounts, are losers?

Because that’s what people who experimented on enslaved women, who advocated for or actually fought in a war for slavery; who, in the most anticlimactic of all of these, refused to let women play in their golf club, are. They’re losers: They lost the battle for dominance over how society views certain things.

Ignoring any moral argument, losers should not get statues or buildings. The Heritage Act was created only as a compromise to remove the Confederate flag from government buildings in the 2000s as a way to ensure that statues of racists and surrenderers - literal losers - would be permanent.

Those who say it is impossible to find an “unproblematic” person to replace statues or building names with are right, to a degree. People are complex and multifaceted; it is a question of how much their good deeds outweigh the bad ones. However, there are an infinite number of trailblazers and heroes whose main and most significant beliefs, values and actions reflect what we as a society have deemed, at some level, brave and respectable.

Why name a recital hall after some dead Georgian who refused to let women into the Masters when it could be named after the first African American player in the U.S. National Championships and Wimbledon, who also happened to be a woman? Althea Gibson is a South Carolina native. Or what about Lucile Ellerbe Godbold, who broke the world's record in eight-pound shot put and was the first woman inducted into the South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame?

Now that Sims is officially having its name changed, we could name it after Dr. Matilda Evans, the first Black woman licensed to practice medicine in the state, and who was the only one in the country to head a state medical association in 1922.

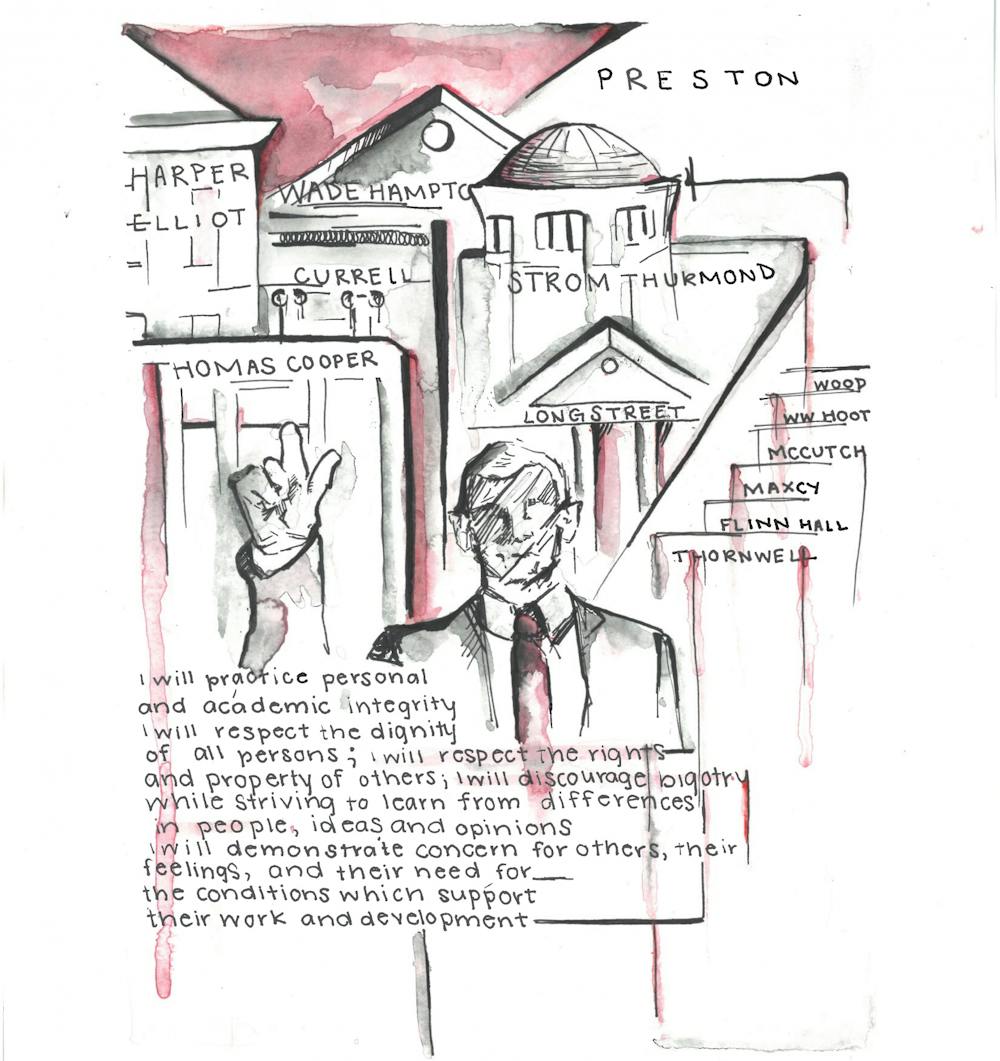

Why must Thornwell Residence Hall, Harper College, Wade Hampton in Women’s Quad or Preston Residential College be named after ardent supporters of slavery? Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld were sisters whose parents were wealthy slave owners and who grew up to become ardent abolitionists. Joseph Hayne Rainey, a South Carolinian as well, was the first Black U.S. Representative to take his seat.

Do the histories of Gibson or Godbold or Evans or the Grimkés or Rainey deserve less honor or attention than those for whom whole buildings are honored, when they present far better moral values to not only USC students but anyone, from anywhere, that may come on our campus?

We walk past the names of these buildings every day. We have class in them for hours, we live in them, and some of us even work in them. Why not make them actually stand for something?