Dorothy Manigault, a Black woman, ran for Homecoming queen in the October 1970 election and placed third. When Luther J. Battiste III saw his classmate's run, he became inspired.

“[Manigault’s success] sort of gave me the idea that with the right type of strategic planning, an African American could win the student body presidency,” Battiste said.

After some time thinking of who'd make the best candidate, Battiste decided on Harry Walker, president of the Association of African American Students (AAAS).

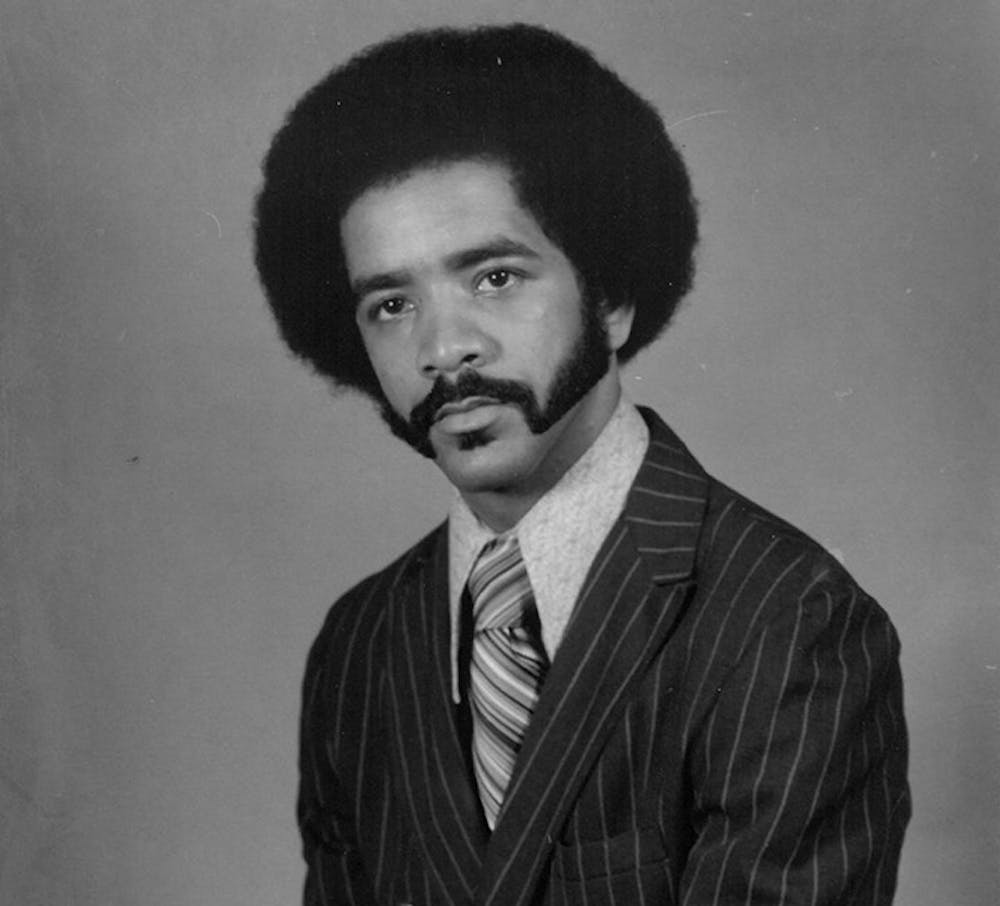

“He was very popular; very handsome; very smart; very articulate; created a good impression; had a big afro. I thought in some ways Harry was very mainstream, but in some ways he was very anti-the-traditional type of candidate for student body president. So, I thought he’d be the perfect candidate,” Battiste said.

But when faced with Battiste’s recommendation, Walker was not sure what to do initially.

“When [Battiste] indicated that he wanted to talk to me about something, I did not have any idea what he wanted to talk about," Walker said. "But during the course of that chat, he brought up that ... he thought the timing was right for the right person to take a run at becoming student body president,” Walker said.

Walkers' campaign took place "during a period of turmoil" in USC and South Carolina, Vickie Eslinger, a cabinet member of Walker's administration, said.

“[We were] trying to change the status of the racism for which our state was so well known," Eslinger said. "Just seeing Harry had an impact on the people in the community because it was a very big deal to be the president of the Student Government."

Walker was a perfect challenger to the status quo at Carolina, Battiste said. He was well-liked, and people were looking for a change politically. Harry fit the bill.

Before beginning to campaign seriously, Walker wanted the support of AAAS. He approached the organization with the idea and, after a few days of discussion, had its support and began his candidacy. Battiste became the campaign manager.

As the March 24, 1971, election date approached, Walker said he was confident in the likelihood of winning either outright or in a runoff, as there was always a runoff.

Once the polls had closed, the campaign met to plan for a runoff. It was during this meeting Walker was told a phone call was waiting for him, he said.

People poured in as Walker took the call in front of Russell House. He answered the phone to hear the voice of Mike Spears, the then-student body president.

“[Spears] told me, ‘Harry I need to tell you this, this is the first time that this has happened,’” Walker said. “He said, ‘There will not be a runoff, you have won this thing outright.’ So, that was very exciting.”

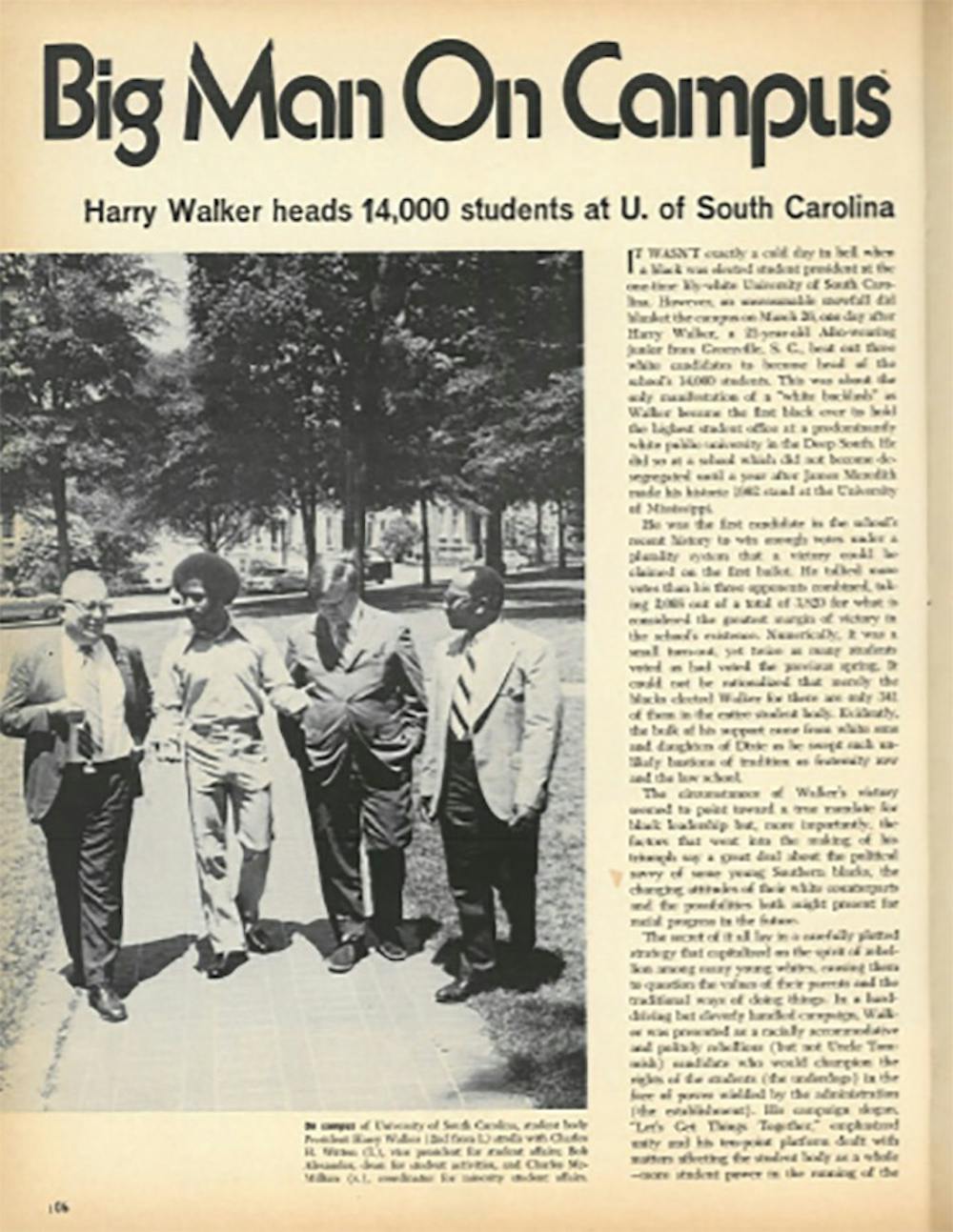

With 2,068 votes, Walker defeated his closest opponent by over 1,200, winning over half of the total votes and the election.

“That was a big deal because [the election] had not happened like that before,” Walker said.

Excitement and celebration spread around campus. The morning after the election, snow fell from the sky over campus, and students continued their festivities in the snow.

“People said it would be a snowy day in Columbia before a Black person got elected president of the student body,” Battiste said.

The excitement around Walker’s election even reached the national level, where he was invited to speak on the Today Show and covered by magazines and news outlets across the nation.

“I was surprised about how far-reaching [the election] was,” Walker said. “I did not [speak on the Today Show] because I did not realize that if I had gone to ask, the administration of USC would’ve sent me there. But I didn’t have any money to fly to New York to be on the Today Show, so there was a telephone interview.”

Walker’s team targeted the issues of campus minorities such as women and international students for the first time at Carolina. Additionally, dining services were targeted for improvements, and the team began the start of a student court system.

"[International students] had never been targeted or gone after before to be active parts of not only the student body, but also people coming in and soliciting their votes,” Walker said. “Many of those conversations with those students were just memorable from the standpoint of inclusion. The thoughts and the thankfulness that they expressed for people just coming and asking them to vote.”

The team targeted women’s health and sexual rights, and other issues faced by women that had not been previously addressed on campus. Eslinger and Walker worked together in addressing these issues.

“He was extremely supportive in helping us start addressing issues that women had,” Eslinger said. “Shockingly, women’s rights was really controversial back then."

Fifty years later, Walker remembers the excitement he felt at the time of his election. Receiving the phone call as the Russell House became more and more crowded. The Gamecock front page with his photo on top of a black rectangle. The snow the day after.

And others remember the election for its impact across the campus and nation.

“I think that a lot of students who came in just parroting their racist and conservative ideas got to know Harry and left the university being willing to make their own decisions based on fact rather than what people told them,” Eslinger said. “People saw [student body president] as kind of a social position, to help themselves. And Harry made a difference. A huge difference.”