Between saliva testing temporarily shutting down on Sept. 3 after a "key lab staffer" fell ill, a high of 1,461 active cases reported on Sept. 4 and having only one lab worker with the government certification necessary to determine if a COVID-19 test was positive, USC experienced several challenges in the fight against COVID-19 last semester.

This semester, USC hired more staff in preparation for the shift to mandatory monthly testing and obtained more equipment. As of March 2, the university has 43 active cases on campus and 1,311 total cases reported on campus since Jan. 1. Last semester, starting on Aug. 1 through Dec. 1, USC had 3,095 total cases.

Since the implementation of mandatory testing this semester, the on-campus positive test rate is 1.67% since Jan. 1, according to the university's COVID-19 dashboard.

Regular testing has made campus safer because more people who test positive are detected and able to be removed from the population, director of Strategic Health Initiatives Rebecca Caldwell said.

"Honestly, it's working, and that's why the positivity rate is low," Caldwell said. "We still grab 20, maybe 20 to 30 people a day, and pull them out of the population, and that means they didn't infect other folks."

Another advantage of doing regular testing is that a potential spike in cases would be detectable, Caldwell said.

"Because thousands of people test per week, about a quarter of us test each week ... if there's a big bit of contagion coming, we're going to get our arms around it pretty quickly," Caldwell said. "As we think towards the concern about variants and other things like that, USC is going to be in a position to know early if we have COVID spreading on campus because we'll be testing."

Mandatory testing has had a roughly 90% compliance rate for each of the four testing groups, according to Caldwell.

The first penalty for missing a deadline results in a warning. A second missed deadline results in a $100 fine. The third missed deadline results in a $250 fine and interim suspension. The fourth missed deadline results in a recommendation of suspension.

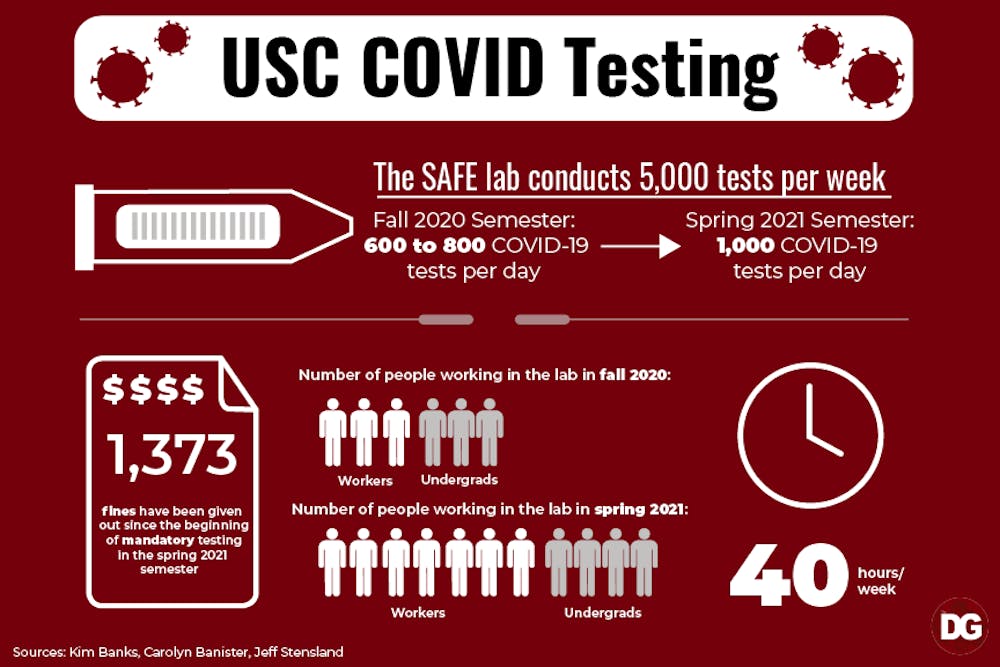

According to a text from university spokesperson Jeff Stensland, 1,373 fines have been given due to students not complying with mandatory testing since Jan. 1. Some of these have been appealed, Stensland said.

Mandatory testing has also resulted in a much higher test volume received by the Diagnostic Genomics Lab since the fall, according to Carolyn Banister, clinical assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy and lab manager.

"It's about 50% more," Banister said. "On a daily basis, we get close to 1,000 a day, so I guess that would average out to about 5,000 a week."

In order to accommodate for the higher testing volume, the university hired more full-time Diagnostic Genomics Lab workers. This semester, the lab has seven full-time workers, at 40 hours a week, which is an increase from the fall semester when there were three, according to Banister.

The Diagnostic Genomics Lab has also turned to automation to accommodate for higher testing volume, with five liquid-handling robots being used in the lab this semester, as opposed to one last semester, according to Banister.

The robots make processing samples much easier because the lab workers don't have to manually pipette samples onto plates, Banister said.

"The plate has 384 different spots on it that we need to put samples onto, and if you do several of those plates a day by hand, it can be very tedious," Banister said. "The robot doesn't mind."

Aside from the full-time staffers, there are four undergraduates working part-time in the Diagnostic Genomics Lab this semester. Fourth-year computer science student Caila Buckhaults worked in the lab last semester and said things have improved a lot since then.

"We were definitely frantic for a while," Buckhaults said. "So, definitely just being able to have more staff to have empty hands, and then donate them exactly whenever we need them, has made everything a lot more calmer."

The goal of the mandatory testing, going forward, is to provide testing to the entire community, Buckhaults said.

"The next [goal] for the lab is to try to open this up for community testing so that we can serve not just our people in our USC family, but to reach out into the city of Columbia and even further," Buckhaults said.