Throughout 2020 and 2021, the USC campus and surrounding Columbia was the site of many protests and demonstrations — some student-led, and some led by outside groups. However, USC has a long history of on-campus protests and activism since its open in 1801.

Elizabeth West, the university archivist at the South Caroliniana Library, said she traces student activism back to before the Civil War, when faculty lived on campus and students could seek out individual professors to rally against.

"Most of the protests that happened in the antebellum years were spontaneous, or smaller, or were typically against a particular professor that they didn't like how he conducted some things — surprised them with an exam, or something like that," West said. "And so the students would gather at night and perform 'tin pan serenades,' where they would bang on their metal plates and cups under the windows of the faculty."

Other demonstrations at South Carolina College included the Great Biscuit Rebellion of 1852, when most of the student body withdrew from the college to protest the poor state of campus dining.

Only four years later in February 1856, tensions between students and Columbia's town marshals led to students raiding the campus library, seizing the cadet arsenal and preparing to fight the city's militia, in an event called the Guard House Riot.

The honor-culture among young men in the South — USC's first female student was not admitted until 1895 — and the closed-off and tight-knit South Carolina College campus in the 19th century might explain why these incidents were so common.

"You had a lot of hotheads, still a lot about the 'honor,' and they were much quicker to challenge each other, I think," West said.

However, the largest mass demonstration in USC history took place in May 1970, called the Months of May.

On May 7, 41 student protestors occupied Russell House and refused to leave in response to the high-profile shootings of anti-war student protestors at Kent State. A 2007 "Peace & Change" case study by researcher Andrew Grose recalls that, when riot police arrived to arrest the demonstrators, the mood around the campus became more sympathetic to the activists' cause.

"Eventually, the police were able to disperse the crowd without using violence or tear gas," Grose wrote, citing an article from The Gamecock the following day. "However, the next day [May 8], a group of 1,000 students marched in front of the state house and called for a pardon of all those arrested in connection with the Russell House incident.

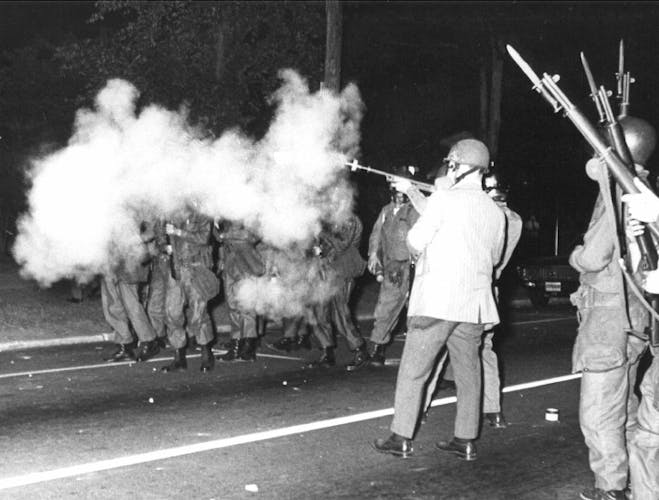

On May 11, 250 protestors who entered the Osborne Administration Building to demand more transparency in how the Russell House activists were being disciplined grew to a crowd of 2,000 demonstrators who faced off against the South Carolina National Guard.

Curious bystanders were attacked and arrested by law enforcement along with real protestors, Gamecock columnist Michael Ball wrote on May 13. For the first of two times that week, tear gas was used against students.

Brett Bursey, a former USC student and self-described "militant radical" who now serves as the director of the South Carolina Progressive Network, said he felt the 1970 protests were driven in part by the clash between USC's overbearing administration and its more outspoken student body, especially on the issue of race.

"There were external factors, certainly, during the early days. It was a white school. Black people couldn't come. All of a sudden, it was a Black school. Then, all of a sudden, it was a white, Jim Crow school," Bursey said. "But there was always a heavy hand of government on the university."

Bursey also traced some of the unrest back to the patriotism that defined baby boomers' upbringings and the apparent disconnect between that and their actual experiences.

"One thing America learned about the '60s and the war in Vietnam was, don't draft middle-class kids," Bursey said. "It took the pressure off of kids that were my age, that were raised well, and believed in democracy and equality and all that stuff. And then you try to practice it, and they put you in jail and beat you up."

USC continues to be the site of protests and activism today.

In the modern era of campus protests, USCPD Captain Eric Grabski said the university is dedicated to defending authorized protestors' freedom of speech.

"We are a public institution, so obviously we have to afford the opportunity for individuals to express their first amendment rights on campus," Grabski said. "The thing is, somebody just can't come on campus and do what they want to do, where they want to do it."