Historical monuments and markers are an important part of telling history to the public, but USC’s markers tell a history that often prioritizes the university's public image over a complete historical record.

One example of this is the board of trustees’ announcement in January that it would name a residence hall after Celia Dial Saxon, a prominent Black educator and civil rights activist who was born into slavery and taught in Columbia.

However, USC's story of Saxon’s life is historically incomplete.

A USC press release announcing the naming described Saxon as a USC "alumni," but that's not an entirely accurate description.

Saxon attended and graduated from the South Carolina State Normal School, a teaching school which was located on the USC campus but was not the same institution — though the two schools did share resources and staff — according to Bobby Donaldson, a USC history professor and the director of the Center of Civil Rights History.

This difference is important to note because Saxon was actually not allowed to attend USC proper because of her gender. Women were not enrolled until 1893.

Saxon graduated from the Normal School in 1877, the same year USC was shut down at the end of Reconstruction.

When the school re-opened three years later, it was re-segregated until 1963. This means that neither Saxon nor the vast majority of the students whom she taught in her 57-year career, would have legally been able to attend USC.

"That's the irony I think we're missing as we elevate her name, that we also have to spend a lot of time thinking thoroughly about the history of discrimination that is quite clear in the records of our university," Donaldson said.

University spokesperson Jeff Stensland said the press release was vetted by the Presidential Commission on University History.

While it's certainly good that the board chose to commemorate Saxon, it was also a missed chance to acknowledge Saxon’s full story.

“There's never a bigger opportunity (than renaming the building) to not just make her accomplishments known, but also to acknowledge the reality of Celia Dial Saxon’s life, which is that she could not attend USC proper,” Katharine Allen, the director of Research at Historic Columbia, said.

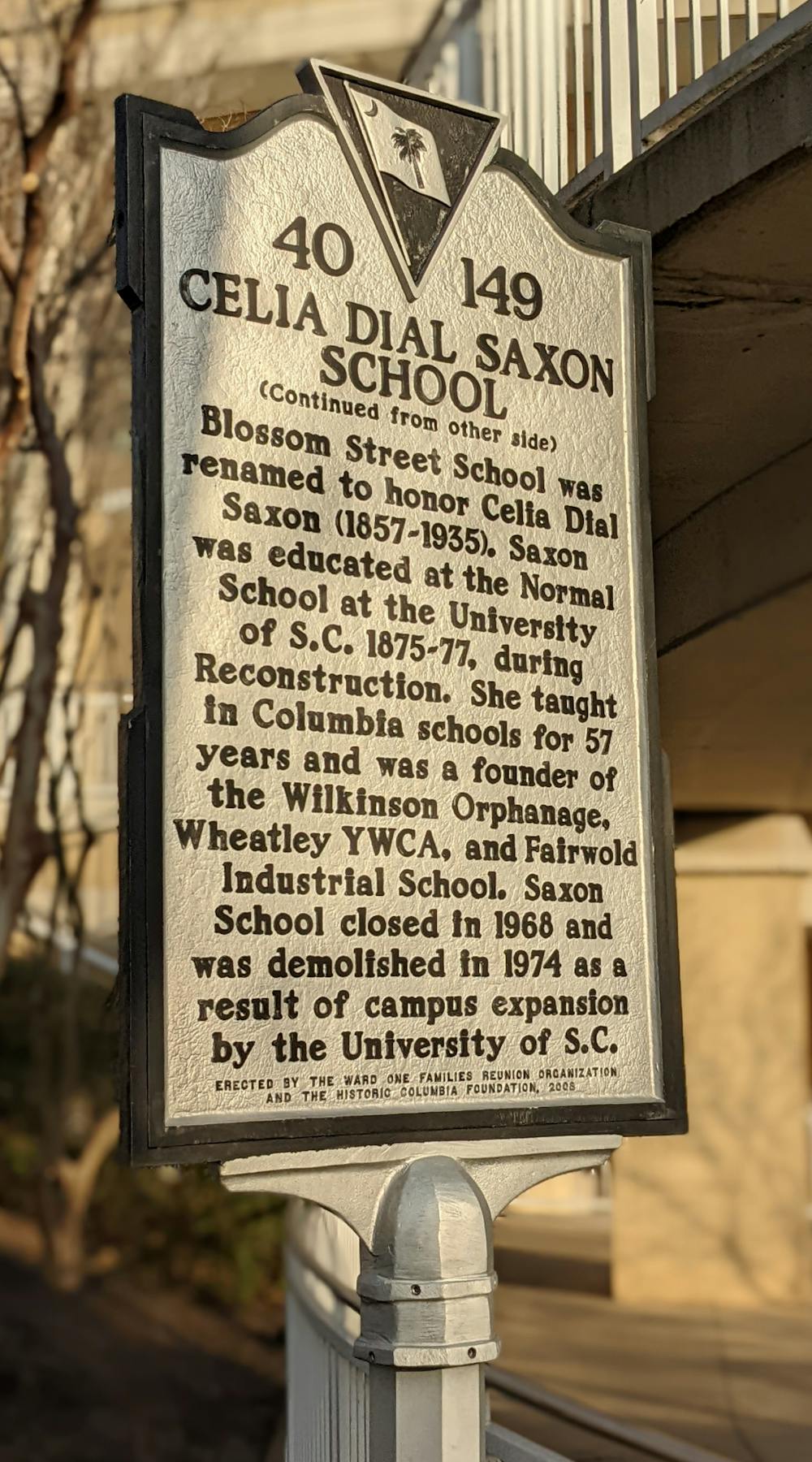

Claiming Saxon as an alumnus is particularly ironic because USC’s westward expansion destroyed the majority-Black Ward One neighborhood, including the closing and demolition of a public school named after Saxon, according to the Presidential Commission on University History's report (which interim university President Harris Pastides ignored).

Today, the Strom Thurmond Wellness and Fitness Center occupies the land where that school once stood, meaning that an elementary school named after a Black teacher was replaced by a gym named after a noted segregationist.

The presidential commission's report even included one request to acknowledge this fact by renaming the gym after Saxon.

Mattie Johnson Roberson, the president of the Ward One Association, wrote a letter asking then-university President Robert Caslen to "demonstrate (USC's) commitment to equity and inclusion by honoring a distinguished graduate and choosing the name, the Celia Dial Saxon Wellness and Fitness Center."

This request was not taken up by USC's leadership, in another sign that the school is reluctant to engage with its history of "leading the bulldozing of Ward One and the bullying of neighborhoods of minorities all over the city,” as Lydia Mattice Brandt, a professor of art history at USC, put it.

700 Lincoln St.'s dedication will not happen until "this summer at the soonest" because of the need to size and order letters for the building, according to Stensland.

Who does USC choose to commemorate?

Saxon is not the only important historical figure that USC has recently decided to honor through a public monument; the board of trustees voted in February to build statues honoring the first students to reintegrate USC in 1963.

Just like how naming a building after Saxon is an excellent move, this decision is an important step towards properly recognizing Robert G. Anderson, Henrie Monteith Treadwell and James L. Solomon Jr.

However, it is important to note that 1963 was not the first time Black students attended USC — during Reconstruction, Black students began to enroll in 1873, but those students are not getting statues.

This fact does not diminish the bravery and importance of the three students who reintegrated campus in 1963, but it does speak to the incompleteness of who the board chooses to honor.

It would be impossible to tell the story of the 1873 Reconstruction integration without also including that the school was re-segregated less than a decade later.

By only commemorating the final integration, USC avoided having to have the difficult conversation about the beginning of USC’s time as a Jim Crow institution and was instead able to focus on the positive story of desegregation, even though that desegregation happened almost a decade after segregation was ruled unconstitutional.

The statue announcement also gave USC positive coverage after facing community dissatisfaction about how the administration ignored the Presidential Commission on University History’s report.

This positivity helped USC strengthen the rosy historical narrative which the university likes to use in its marketing strategy — Pastides’ reaction to the statue news was to connect integration to the university’s new “Remarkable We” marketing campaign.

How does USC remember its first Black professor?

Even the Richard Greener statue, which commemorates the first Black professor at USC, was a missed opportunity for better engagement with USC’s history.

An ad-hoc committee of faculty worked for six years to push the Greener statue project forward, and one part of their plan was a larger project to research Reconstruction-era USC and make those findings available to other scholars and the general public.

That didn’t happen.

After Pastides decided to fund and support the statue, his support did not include funding or willingness for deeper research into USC’s Reconstruction history, according to the new book “Invisible No More,” which tells the story of Black Americans at USC.

“Scholarship that reckoned with the standing narrative of the university’s Reconstruction-era history was not part of the administration’s implementation of the Greener statue,” Allen and Brandt wrote in their chapter of “Invisible No More.” “Neither the board of trustees nor Pastides included any funding or support for research that would encourage comprehensive revision of the institution’s narrative as a part of the statue’s construction.”

The current commemoration doesn't even tell the whole story of Greener's time on campus.

"We talk about the statue of Richard Greener," Donaldson said. "We don't talk about how he lost his job, how he was dismissed from his position."

Greener was removed from his position in 1877, the same year Reconstruction ended and Wade Hampton was elected Governor of South Carolina.

Hampton was a Confederate general, a slave owner and a supporter of the KKK, according to the Presidential Commission of University History. He is also the namesake of the Wade Hampton wing of the Women's Quad on USC's campus, meaning that USC doesn't fully commemorate how Greener left the school but does honor the man who re-segregated it.

How does USC construct its public markers?

A similar story unfolded with the process of approving the two plaques on the Horseshoe that briefly describe the history of slavery on USC’s campus.

The plaques, which were finally installed in 2017, were in part the result of a student protest campaign in 2015 called USC 2020 Vision, which laid out various demands about social justice on campus, including that the university reckons with its history of slavery.

Despite the fact that stakeholders around Pastides were “clearly responding to (the 2020 Vision campaign),” according to Brandt, Pastides denied that the protest played a role in the process of approving the plaques.

Refusing to acknowledge the role that student activists played in this process is another example of the positive historical narrative that the administration tries to craft about USC. This time, the administration centered itself as the origins of change instead of the students who were criticizing its inaction.

“Of course progress takes time, but crafting a response in this way ultimately sends the message that the administration’s actions are not at all influenced by calls for change coming from the community of students, faculty, and staff at the University,” Claire Randall, a former USC student who helped organize the USC 2020 Vision protest, wrote in her senior honors thesis about the campaign.

The text of the plaques originated from a USC history senior research seminar taught by Robert Weyeneth in fall 2010. Graduate students continued the research the next spring and created a website that challenged the university’s preferred narratives about slavery.

Language from that website made up the bulk of the original proposal for the plaques’ text, but by the time the plaques even were finally installed in 2017, a university committee had simplified the text and made them less forceful.

“References to the college’s ‘landscape of slavery,’ the role of the college’s faculty and students in advocating for slavery, and even the duties performed by enslaved people on campus had been removed,” according to Allen and Brandt in “Invisible No More.”

All of these examples of historical markers make a public historical argument — they define the terms of how people understand, discuss and debate USC’s history.

When these markers tell an incomplete story, as USC’s often do, they leave the USC community ill-equipped to understand their institution’s history and to right its many historical wrongs.

As the example of the history seminars show, there are students and faculty on campus who want to dig into USC’s long and complicated history and tell that story to the public.

USC needs an administration and a board of trustees who is willing to do the same.