While standing in the auditorium of what was once Columbia’s first public high school for African American students and a landmark for civil rights activists, Imani Perry delivered a personal and powerful narrative about growing up and traveling thorough the American South.

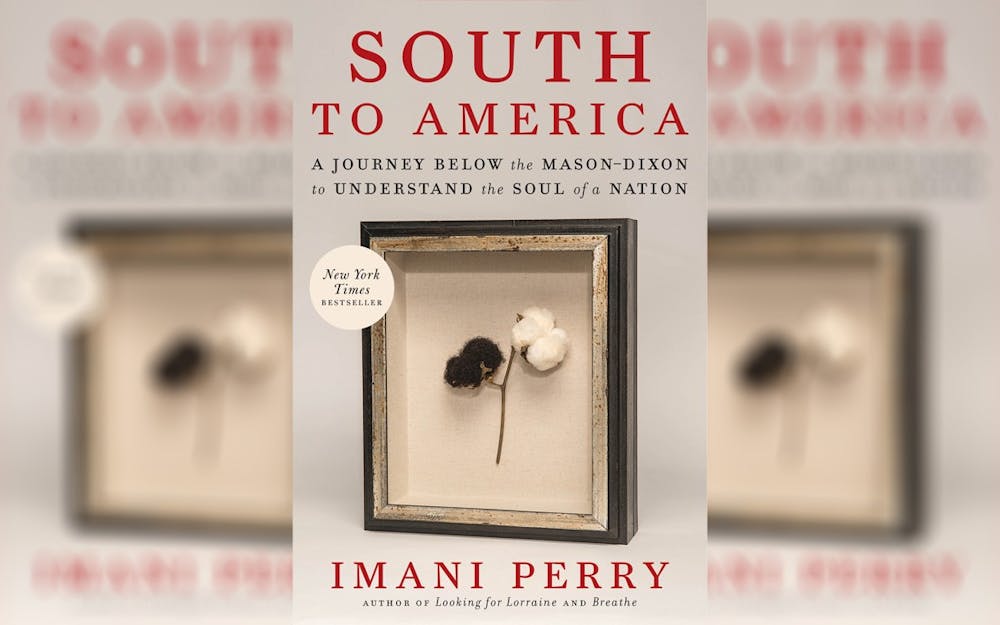

In her visit to USC on Feb. 22, Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, spoke about her latest book “South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation," which argues that the history of the South is essential for understanding the rest of the country.

Perry studies law, literature and culture, with a focus on Black thought and its connections and resistance to political and social domination.

Her talk was hosted by the USC Humanities Collaborative, a collaboration between USC faculty which seeks to facilitate interdisciplinary work and outreach between the humanities departments at USC.

“Our goal is to promote the humanities and humanities forms of inquiry very widely across campus, in the community and throughout the state,” Holly Crocker, a USC English professor and the faculty leader of the Humanities Collaborative, said.

One part of this outreach is publicly hosting guest speakers whose work speaks to contemporary issues and has appeal to audiences both inside and outside of USC, according to Crocker.

Perry’s talk, which centered around “South to America,” had a loosely a narrative travelogue which explores Perry’s experiences throughout the South. She used those experiences to help explain “what it means to walk through history” and to argue that the South plays a central role to U.S. history and culture.

It's not a traditional academic history, which Perry said allows it to emotionally connect with its audience better. By prompting an emotional response, even if that response is at times anger, Perry said that really meaningful writing is able to resonate with its readers.

One of the stories Perry shared during her talk and in her book was about her experience taking a Lyft home from the Birmingham, Alabama airport.

Her Lyft driver was a white man who had worked as a coal miner for decades. Perry talked about how, during her ride, she thought about both the hardships that the driver must have experienced as a coal miner, but also how the relationship between him and Perry — a younger Black woman — was colored by the white nationalist logic which he would have grown up inside of.

“I imagined the ideology behind Jim Crow justice in his mind,” Perry said during her talk. “I didn’t know that’s how he thought about anything, but I imagined it, because part of the lesson for a Black girl/woman coming of age in the South is that you have to have a defensive logic when you move about the world, you have to anticipate the white supremacist gaze, the prospect of racial violence.”

When the Lyft arrived at Perry’s destination, the driver waited for her to safely get inside the house.

“It was important to me to be able to depict that tenderness,” Perry said. “Because part of the complication in the story is that there’s a remarkable intimacy across the color lines … as well as a history of incredible violence.”

Her talk discussed the complicated way in which real life in the South does not always line up with the “mythology” that people have constructed about the region and its inhabitants.

Perry said she also has to address those mythologies while at Princeton, whether she’s teaching about the South specifically or more broadly about African-American history and American law.

“We have these shorthands in our culture that often stand in the way of deep study and exploration and understanding,” Perry said. “So some of it is sort of getting past the surface narratives to actually do some deep examination, to understand also how central the South was to the development of U.S. law, U.S. politics.”

Tishon Pugh, a fourth-year anthropology major, said she appreciated that aspect of Perry’s work.

“People try and put the South as this one thing, but I think with this book and with (Perry’s) talk, I’m looking at the South a little differently,” Pugh said.

Before her talk, Perry was able to tour some of USC’s historical sites like the Booker T. Washington building, and she urged students to embrace the opportunities for historical, social and political work at USC.

“I would just sort of encourage USC students to understand how uniquely situated they are to have access to scholars and resources that are doing such important historical work,” Perry said. “They are literally in the center of so much critical U.S. history in Columbia.”