After a lifetime of working outside, Herrick Brown found himself in a dark, windowless office in Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution.

His days creating enclosures at Riverbanks Zoo in Columbia, S.C., and camping on remote islands off South Carolina’s coast to study undocumented ecosystems seemed to be over, replaced with managing research databases and combing through scattered scientific records in the Smithsonian’s many libraries.

One day in one of the libraries, Brown discovered some of the first biological records from what would eventually become the United States. He read centuries-old accounts from some of the first botanists exploring the wilderness in what is today the American Southeast.

“That then opened my eyes to the fact that where I was from had one of the longest-standing manifestations of natural history research — like people interested in nature and being in the outside world and that sort of thing,” Brown said.

Herrick made a decision: He was going back to South Carolina.

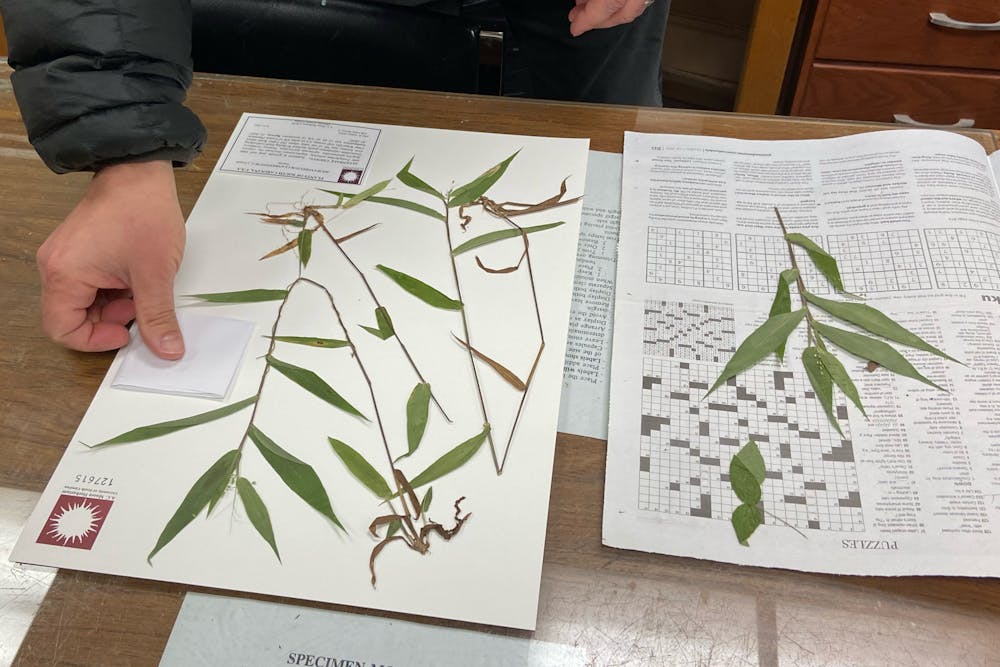

Among rows of filing cabinets containing more than 140,000 dried plant specimens, student workers and researchers from across the state create new pressings and input records into online databases. They work to preserve specimens from around the world — some very rare or extinct and decades old.

These records are used to track plant populations and in research projects across the state and internationally.

Here in the organized clutter of the University of South Carolina’s A.C. Moore Herbarium, Brown now serves as curator from an office in the back of the room.

Brown runs the herbarium — the state’s largest — while also serving as a resource for those who use it.

Fourth-year marine biology student, Avery Browning, photographs plant specimens and inputs data into the herbarium’s database. She said she feels her voice matters in the herbarium more than with other classes and jobs.

Browning said she once found small crabs pressed in with an algae sample she was working on and thought they should be identified and associated with the species of algae.

“I told him that idea,” Browning said. “I wasn't sure if he’d like it and he was instantly like, ‘No, that's a good idea. Let's do that.’”

Browning said Brown immediately put her into contact with a professor who could help.

Brown was the son of Army brats. His father was constantly looking for opportunities to play with small things that lived outside his Columbia, S.C., home and would drive him on the weekends to catch critters with broomsticks, wire coat hangers and knotted-up pantyhose.

Brown crafted enclosures for the critters he caught — such as a bathtub his father helped him bury in the backyard to stock with fish. These usually included some sort of plant life for the animals to live alongside.

After graduating from USC with a biology degree in 1996, Brown began doing volunteer work at Riverbanks Zoo, creating realistic exhibits for the animals.

“That got me more interested in this sort of the whole, the whole package — the ecology of it — the habitat and all the different little interactions and nuances,” Brown said. “What does a particular animal need when it's out in the wild, so to speak? And how does it interact with various plants and other sorts of things that grow where it lives?”

The zoo led him to fieldwork with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources (DNR). After graduate school at USC, he wanted a change and followed his now-wife to D.C., where he ended up in the windowless office at the Smithsonian.

After his epiphany in the library in 2007, he and his wife headed back south. He returned to DNR while also working on his Ph.D., again at USC. Brown was hired at the herbarium in 2019.

He now spends his days among the dried plant pressings and various students, researchers and DNR employees looking through the herbarium’s thousands of specimens. He also teaches both on and off-campus.

Csilla Czako, a database technician for DNR, works to digitize data on plant life across the state. This work brings her into the herbarium often.

She also teamed up with Brown to host a virtual children’s educational program through the Richland County Library. With the program taking place at the end of October, Herrick had the idea to make the presentation especially seasonal.

“He talked about how the herbarium is like, technically, a plant morgue, so (with) dead plants,” Czako said. “He turned off the lights when we came into the herbarium on the Zoom meeting, and then we hid and we're screaming. We were like the ghost of the plants, and the kids loved it a lot.”

Czako said people in the herbarium community nationwide ask Brown for advice.

“I think part of it is because he is so accommodating and so willing to help,” Czako said.

While Brown said he wants to get back out into the field more often, his work in the herbarium is as interesting as much as it can be overwhelming.

“Just the potential for growth that this collection is experiencing is also pretty exciting,” Brown said. “I hope to be here when we find new digs or are able to expand in a new space or something like that and just make it more functional and sort of broadcast our existence to a wider audience.”

Correction (April 13, 2022 at 3:20 p.m.): A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to the Smithsonian Institution as “the Smithsonian Institute.” The error has been corrected.