USC researchers are working with Still Hopes retirement community in West Columbia to measure walking patterns and develop new technology that will help clinicians better care for the elderly.

The project, a collaborative effort between researchers with USC's College of Engineering and Computing and the Arnold School of Public Health, aims to monitor health parameters through subjects’ footsteps using floor sensors in their apartments. Development of the sensors began four years ago with a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH), while the testing and data collection started at Still Hopes six months ago.

“A lot of clinicians ... talked about walking speed as the sixth vital sign," Dr. Stacy Fritz, a physical therapist in training, said. "It tells you about underlying (health) factors that are going on.”

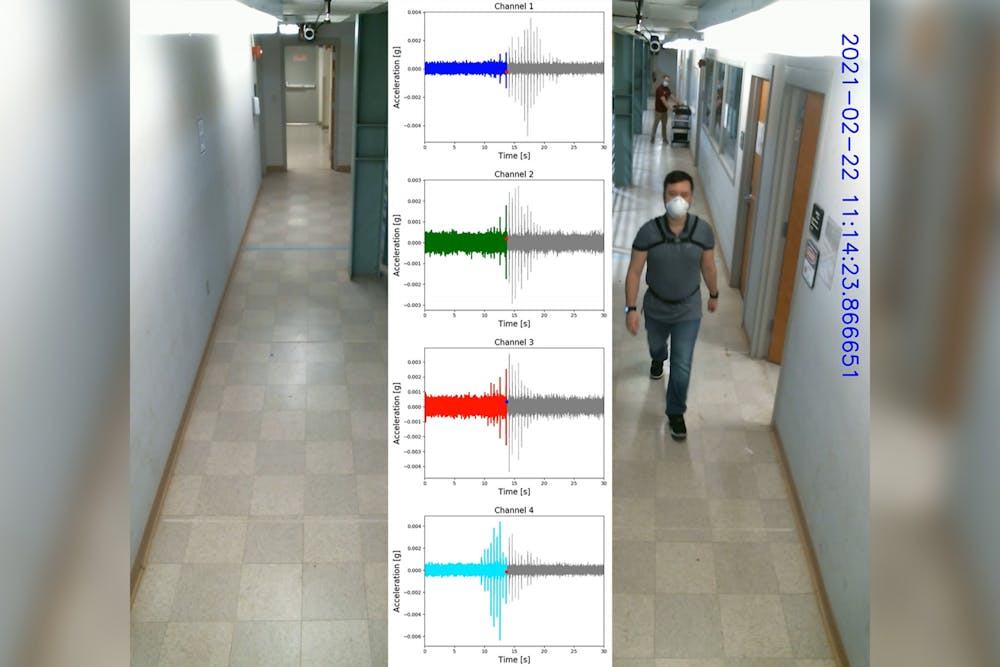

Fritz and her team of health scientists study walking using sensors designed by her counterpart, civil engineer Dr. Juan Caicedo. Caicedo’s team developed and built the sensors, called 'accelerometers,' that track footsteps in the participants’ homes by measuring vertical displacement on the floor.

According to Dr. Yohanna Mejia Cruz, a civil engineer on Caidedo's team, the development of the sensors aims to serve as a tool for clinicians to use when working with elderly patients, which has become increasingly important for healthcare professionals in recent years.

The need for technology that helps clinicians treat elderly patients is growing with the United States's increasing older population. By 2050, 20% of the U.S. are going to be aged 65 years old or older, Cruz said.

According to Fritz, there are already signaling technologies in place for elderly individuals to use in the incident of a fall and smart devices that can monitor walking speed, but those technologies all require individuals to remember to wear or utilize them.

This can become an issue when working with older patients as memory problems may cause them to forget to wear their device, and some technologies may be too complicated to use. The sensors being tested at Still Hopes take away the need for individuals to remember them, as they monitor the floor vibrations automatically Fritz said.

While the sensors are installed at Still Hopes and collecting data, the researchers are still working through how to process what they collect.

“That’s easy, to put the sensors and you just wait for them to record the data, right? The tricky part comes from what are you going to do to the data, what are the techniques that you’re going to use to extract the information that you need? For instance, cadence, or walking speed,” Cruz said.

In order for the health scientists to detect changes in cadence and walking speed, the civil engineers turn the floor vibration graphs produced by the sensors into statistical graphs so unusual changes in gait can be measured.

“Neither of us could explore this alone. [Caicedo] needed someone who understood the human side. I absolutely needed someone who could understand the technology side,” Fritz said.

Since the new sensory technology is still being tested, the research team is seeking to create something that will be of greater use to clinicians in the future, Garrett Hainline, a third-year PhD student and apprentice of Fritz, said.

“It’s not really going to immediately benefit [the participants]. We need your help to help people in the future,” Hainline said.

To support both clinicians and future patients, the team held a recruitment event at Still Hopes on Thursday in hopes of educating individuals and obtaining more participants who would be willing to have sensors placed in their homes. More participants will allow for more data that would benefit the project’s progres, Hainline said.

While there is a concern about the willingness of residents to participate, Hainline thinks “people like to help people."

After installing the sensors into more homes, the team hopes to have enough data to create a patented device that can be utilized universally in healthcare.

“What I hope that we can do is write the algorithms, test the algorithms, write the ideas, write the fundamentals and then produce that intellectual property in the form of patents that then companies go and commercialize,” Caicedo said.

To get the project closer to a finished product for commercialization, the team is seeking to request an extension for their grant with the NIH. Once the project is completed, it will demonstrate the benefits of interdisciplinary research and the possibilities of both health sciences and civil engineering.

“I never thought that I could create such an impact directly to a person’s health," Cruz said. "As a civil engineer, you’d never think that you can actually do that."