The video of 29-year-old Tyre Nichols being brutally beaten marks another person of color being killed at the hands of police officers, and it adds to the seemingly endless stream of videos plastered on the internet and treated like theatre of people of color being killed. Exposure to such cruelty can cause mental health challenges, especially among people of color, while doing nothing to actually address the problem of police brutality.

The latest release of a Black man being beaten, chased down and dehumanized has made its way online and into the hands of news networks. On the evening of Jan. 7, Nichols was stopped by five Memphis police officers for alleged reckless driving. As the scene escalated, what followed was approximately three minutes of Nichols being so brutally beaten that he was later hospitalized. After three days in critical condition, he died.

On Jan. 27, the city of Memphis publicly released footage of the beating, which was caught on the officers' body cameras. The video shows the five police officers kicking, taunting, punching and beating Nichols with a baton while he screams for them to stop, occasionally calling for his mother. This is a chilling parallel to the George Floyd video that was released in 2020.

Before the release of Nichols' video, police issued a “countdown” until the violent footage would be released to the public. The way social media and cable news networks treated the publication of the horrific video was nearly indistinguishable from a new product release, or movie premiere. They promoted that the video would be horrific, and the recordings did not fall short of expectations.

With many people already having watched the Nichols video due to its heavy circulation online and on television, it is important to remember that watching this display of police brutality is not an obligation.

For people of color, repeatedly seeing videos of someone who could very well be you, a family member or a friend getting assaulted or killed by police carries a different weight than for our white counterparts, who are permitted a certain level of detachment that people of color are not.

A 2018 study published by The Lancet revealed that police killings of unarmed Black Americans effect mental health among Black American adults and could cause additional poor mental health days. However, the same impact was not seen for white Americans.

Nana Ama Boateng, a first-year graduate student in the Clinical-Community Psychology Program at USC, studies the effects these videos have on Black Americans.

Boateng's research focuses on a term called vicarious racism that results from police brutality on social media. She looks at the connection between past entices of police brutality and Black Americans' distress after exposure to them.

According to Boateng, Vicarious racism is secondhand exposure to racial discrimination and prejudice directed at another individual. Whether in-person, online or through word of mouth, exposure to police brutality can cause anxiety, a heightened sense of danger, anger, sadness, mood swings and decreased faith in institutions.

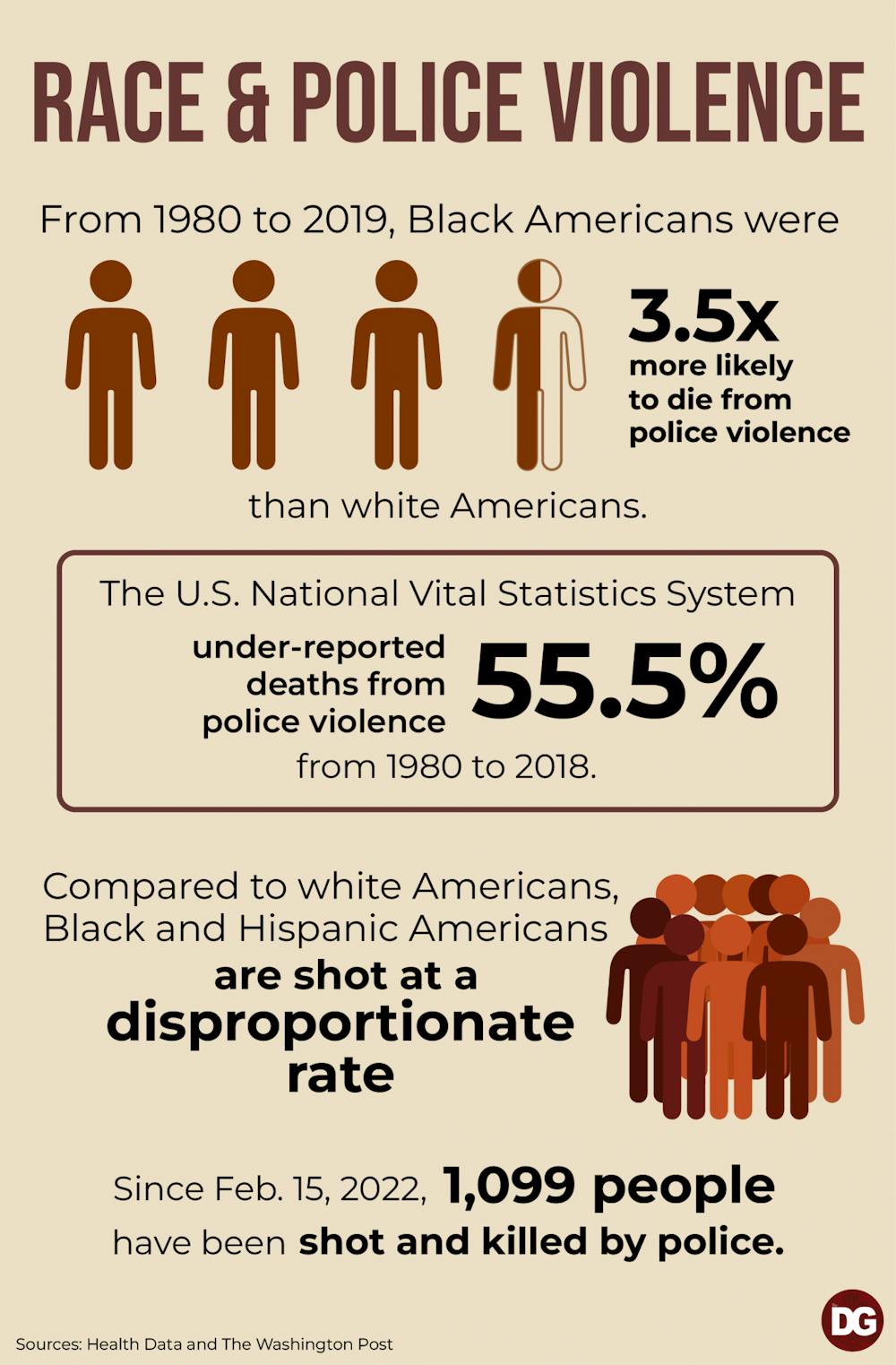

This is a term customarily associated with first responders. However, with the overabundance of people of color getting killed by police officers, the term is now used to describe a form of trauma Black Americans suffer from as well. Being exposed to or witnessing these acts, like in a video, can onset this trauma. Given that 1 in every 1,000 Black men is killed by the police in their lifetime, it’s evident how this pain builds up. Black people have a deep-rooted connection to these videos that extends past mere empathy for a fellow human.

“That (Nichols) video made me feel like I didn’t matter. I felt like, at any possible point, I could lose my life if I get behind a wheel and I get stopped by a cop,” Boateng said.

Although completely avoiding videos of police brutality can be difficult, there are precautions one can take to lessen them. For instance, utilizing features on apps that allow tailored content. Individuals can mute certain profiles and keywords included in tweets, or even unfollow or block profiles that share related content.

Reading information and updates from reputable news sources can keep you up to date on the issue without having to experience the discomfort of watching the content.

However, while these precautions can help limit exposure, they are not foolproof. If a person of color does find themselves experiencing mental health issues after watching a video of police brutality, there are resources that can help them cope.

“We know that one of the possible solutions that help mend one of this is collective coping effects ... meeting with a group to unpack how the video made you feel," Boateng said. "Am I internalizing anything? If I'm internalizing something, who can I talk to? What can I do to release whatever emotion I’m feeling?"

Boateng also said it is important for people of color to identify their support system when feeling negative emotions after watching videos of police brutality, whether it’s in our inner groups, community or even at the institutional level.

Deciding not to watch videos of police brutality does not mean sacrificing being a part of the solution and making your voice heard, there are other ways to be supportive.

“I don’t think it’s absolutely necessary for people to watch the (Nichols) video," Boateng said. "But I think being aware that something like this happened is important.”

Attending protests, volunteering for organizations combating police brutality or attending city council meetings addressing policing and public safety are ways to proactively impact your community without watching videos of police brutality.

Watching videos of people of color being brutally beaten and killed by police does not necessarily educate individuals, expose the world to unknown injustices or fix the problem of people of color being disproportionally killed because of the color of their skin.

If this was the case, Mamie Till-Mobley exposing her son, Emmett Till's, morbidly beaten body for the world to see after he was lynched or the video of Rodney King's horrific beating after being stopped by four policemen, would have long ago fixed the problem. Instead, these videos and the ways they are promoted supply psychological harm to the very people they're trying to help.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Nichols' name.