The annual Gamecock-Tiger football game is a cornerstone of the South Carolina and Clemson's rivalry each season. But while football has been central to the rocky relationship between the two schools, it does not tell the full story.

With its origins dating back to the late 19th century, the rivalry between the University of South Carolina and Clemson University has stood the test of time and remains a central part of life in the Palmetto State.

Specific events — namely, political disputes and two football games in 1986 and 1902 — have played integral roles in shaping the rivalry into what it is today.

Origins off the field

The University of South Carolina spent the first 88 years of its existence without its rival school, which was not established until 1889.

But Elizabeth West, the university archivist at the South Caroliniana Library, said bad blood existed between the institutions well before Clemson University's founding. Political motivations behind what the Palmetto State’s flagship college should look like are at the heart of the rivalry’s origins, she said.

“During the last half of the 19th century, South Carolina College — the University of South Carolina — was a ‘political football,’ so to speak, as different politicians gained power in the state legislature, there were different views of what the university should be,” West said.

Following the American Civil War, the United States experienced a period of history called Reconstruction, where significant changes were made to the nation’s social and political structures.

South Carolina College, as it was known at the time, followed suit. University Historian Evan Faulkenbury said the college became “a model for integrated interracial education” between 1874 and 1877.

It would not remain that way for long, Faulkenbury said.

“For those three years, we had Black students, Black faculty. So, USC was unique among Southern public institutions that kind of became a democratic institution,” Faulkenbury said. “That was quickly reversed in 1877 at the end of Reconstruction. The state’s political leaders thereafter saw USC as like, ‘How dare you let Black people onto your campus and pay your professors so much? We’re going to start our own thing out west.'”

Around this time, the state of South Carolina underwent an agrarian movement led by Ben Tillman, a political figure who would eventually be pivotal in Clemson's founding. Tillman and other leaders wanted to empower farmers and believed USC was not representative of their views, Faulkenbury said.

“A lot of those leaders saw USC as this elitist, intellectual, not really serious for the everyday, blue-collar, farmer-type South Carolinian,” Faulkenbury said.

South Carolina's agrarian movement coincided with the death of Thomas Green Clemson, a prominent diplomat, engineer and artist. Clemson, like Tillman, advocated for the establishment of an agricultural college in the state and, in his will, allowed for his estate to become Clemson Agricultural College, which was originally an all-white, all-male military school.

The founding of Clemson led to a dramatic shift in the government's priorities in terms of higher education funding, Faulkenbury said.

"USC people and its leaders in the state legislature kind of saw almost like a betrayal of state higher education by all the funneling going to Clemson," Faulkenbury said. "Clemson really remained the central player for a good portion of the first half of the 20th century with state money (and) state leadership being more inclined to help Clemson out than USC."

Right before the turn of the century, a new venue where each school could demonstrate its superiority over the other — the gridiron — emerged.

“It was an ugly history,” Faulkenbury said. “And then football, when it started being played in 1894, became kind of an outlet for these emotions — to beat up on each other.”

A football rivalry is born

When South Carolina and Clemson played in their first-ever football game in 1896, the sport was much different than it is today.

During this era of football, committing penalties resulted in harsh punishments — if a player committed an offsides penalty, for example, possession of the ball would change. Specific scoring plays also resulted in a different number of points — touchdowns were 4 points, field goals were 5 and conversions and safeties were 2.

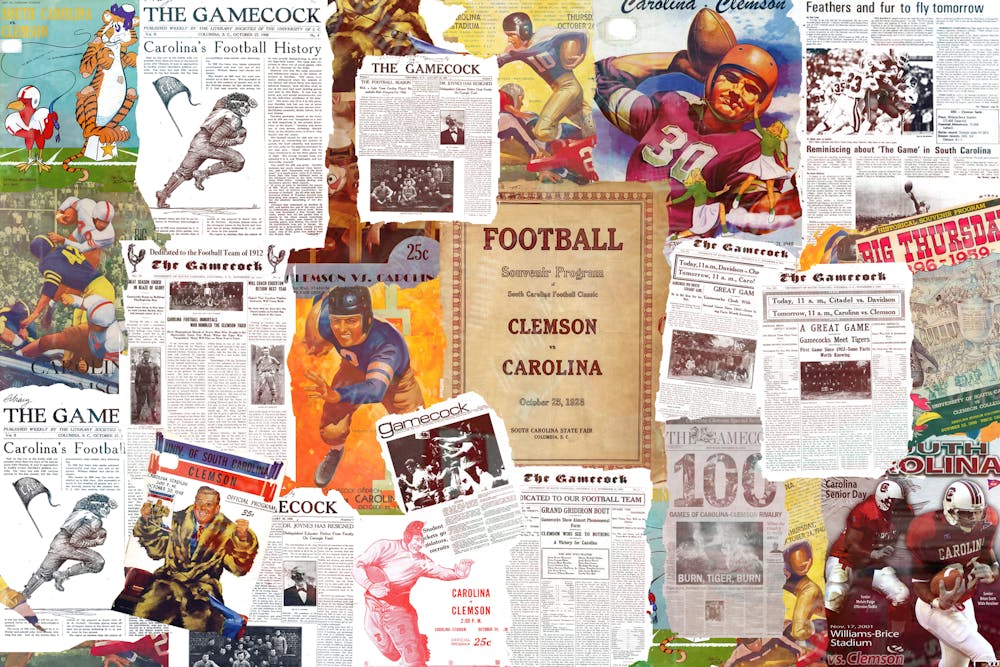

In its infancy, the South Carolina-Clemson contest was one of many events that were part of the “Big Thursday” festivities at the South Carolina State Fair. The game would take place the same weekend as the fair until 1959.

Although the game was not a standalone event, “Big Saturday” was a big draw for South Carolinians across the state, West said.

“It was practically a state holiday. People would ride trains … and they had ticket specials for them to come to the State Fair and to Big Thursday,” West said. “It really was this monumental event.”

South Carolina and Clemson’s first rivalry matchup was witnessed by a “crowd of over 2,000,” according to an account published in The State the day after the game on Nov. 13, 1896.

Kristopher Dempster and Christopher Barstow — who both serve as librarians and career coaches at the Richland Library — co-wrote a blog post about this game on the library’s website last fall. Based on accounts he had read of the game, fans from both teams were excited about the game due to its novelty in the region, Dempster said.

“What was more popular was actually the State Fair … And I believe they had some horse racing along with it, too. That was more popular back then, as well,” Dempster said. “Football was basically new to the South. I think Carolina started in 1892, their first game, and I think they only had one or two games per year. And in 1894, I think it was, Clemson had their first game.”

In what would prove to be a rainy contest, South Carolina emerged victorious by a 12-6 score. N.W. Brooker is credited with being the first player to record a touchdown in the rivalry, and Canston Foster provided South Carolina with the game-winning score in the second half.

After the game, the author of the article in The State also made an observation of the Clemson players’ demeanor after the game, saying they “take their fate very gracefully with no show of ill feeling.”

Fiery tempers and flames

That would not be the case when the two teams met six years later, though, in what would become one of the most notable moments in the rivalry's history.

South Carolina and Clemson met four more times after their initial meeting in 1896, and the Tigers claimed victories in all four of them. That streak ended on Dec. 6, 1902, when South Carolina snapped its losing streak and claimed its second-ever win over Clemson by a 12-8 score.

West said South Carolina students celebrated the upset victory by taking a drawing of "a gamecock crowing over a beaten Tiger" that had been displayed in a local shop and taking it around Columbia. Clemson students and fans were offended by the gesture, telling the students not to bring the drawing to a parade on Main Street that was taking place the next day.

"So naturally, the students brought the drawing in the parade the next day," West said.

Clemson cadets participating in the parade then decided that, once the event was over, they would march onto South Carolina’s campus with weapons brandished to claim the drawing, West said.

“The newspapers report 200-300 Clemson students and fans matched onto campus, and about three dozen or so of our students found out about it and hastily armed themselves with knives and pistols,” West said. “They hunkered down behind the Horseshoe wall to defend the campus.”

West said no blood was shed, though, as local police diffused the situation before any violence took place. The police did so by burning the drawing in front of both parties, which led to the creation of USC’s Tiger Burn tradition that continues to this day.

While the incident resulted in a seven-year suspension of the rivalry, it also led to the creation of South Carolina's nickname.

"We didn't have a mascot up until that time. (We) hadn't really settled on one," West said. "After that event, the newspapers and others started calling us the Gamecocks, and the next year, next football season, we were the Gamecocks."

The rivalry's legacy

The rivalry between South Carolina and Clemson has taken many new forms since the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Beginning in 1960, the location of the two schools' football games alternated between Columbia and Clemson, rather than being played at the South Carolina State Fairgrounds each season. West said the advent of television during this period of time helped the South Carolina-Clemson rivalry grow in prominence.

"I think that, probably, the grand spectacle of Big Thursday really pumped that up for so many years. It made it into this big event before you really got into the modern televised spectacles and TV ratings and all those kinds of things and major stadiums," West said. "I think that really helped keep it really going."

In 2014, the game was renamed the Palmetto Bowl while the Gamecocks and the Tigers were in the midst of a 111-season streak of playing against each other — the longest of any two opponents not playing in the same conference.

The rivalry has extended beyond just football, too. The first Carolina-Clemson Blood Drive took place in 1984, and the first Palmetto Series — a competition sponsored by the South Carolina Education Lottery that encompasses more sports — began in 2015.

The growth both universities have experienced over time has similarly caused the rivalry to also grow, West said.

"You get a boost in the post-war baby boom, so you get bigger schools, expanding schools, more alumni for the programs to support athletic programs and football being in the South was just the sport," West said. "It just kept building and building and building, even as Big Thursday started to wane and Clemson wanted to go to the traditional alternating locations because they were missing out on all of the financial benefits that USC and Columbia were getting."

She also said the rivalry’s versatility is what continues to make it strong to this day.

“It was just a great rivalry and really intense in our small state,” West said. “It just bleeds into a lot of other aspects of the state’s culture.”